'Gerry Wedd, Kitschen (sic) Man' published in the Journal of Australian ceramics Vol 56 # 3, 2017

JamFactory ICON - Gerry Wedd ‘Kitschen Man’ – review of the 2016 touring exhibition.

Awarding the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan was always going to be controversial, but things really ramped up given his tardiness in formally accepting the award. He did eventually fulfil his obligations by having the banquet speech delivered on his behalf by the US ambassador to Sweden, and then by finally giving his Nobel lecture, via satellite, just a few days short of the deadline that would have seen him forfeit 1.2 million dollars in prizemoney (now that really would have been controversial …) It was all a bit unconventional, but the committee probably should have remembered that this was the guy who went from roots folk icon to rock ‘n roll at Newport in 1965, reacting to a shocked audience by telling the band to … ‘play it fucking loud.’ At least he didn’t say that to the Nobel committee.

Both of Dylan’s speeches are now on the internet, and – again somewhat controversially – he is being accused of plagiarising some of the content from an online resource called Sparknotes, which should hardly be a surprise given that Dylan’s penchant for appropriation has underpinned a great deal of his recent output. The trick, and Gerry knows this better than most, is to borrow well, to do it in a way that pays back the debt.

I actually think that both of Dylan’s speeches are great insofar as they are very entertaining and, as an aside to the controversy surrounding his award, he does address the relative values that society places on art forms: high and low; the popular or the wilfully obscure; the good, the bad and the ugly.

In his banquet speech, Dylan says that he ‘ … began to think about William Shakespeare, the great literary figure. I would reckon he thought of himself as a dramatist. The thought that he was writing literature couldn’t have entered his head. His words were written for the stage. Meant to be spoken not read. When he was writing Hamlet, I’m sure he was thinking about a lot of different things. “Who are the right actors for these roles?” “How should this be staged?” “Do I really want to set this in Denmark?” … and … “Where am I going to get a human skull?”’.

Dylan goes on to say that his own creative process is just as riddled with questions that are often about the nuts and bolts that underpin making art, and that he hasn’t really had the time to sit back and ask himself if what he did counted as literature, but if the Academy had reached that conclusion then it was OK with him and he was grateful.

Bob Dylan deputised Patti Smith to perform in his stead at the ceremony and she forgot the words to ‘A Hard Rains Gonna Fall’ half way through the performance. More controversy, or just a storm in a teacup? In twenty, thirty, fifty-year’s time people won’t be talking about this stuff but they will still be listening to Bob Dylan. Art’s like that.

Anyone who knows Gerry and has seen him work will immediately get, at least in a general sense, why I mention Dylan, in that whenever Gerry is making the music is playing, but the way Dylan talks about process is also interesting because, at least in my experience, what ends up driving artists is the process of making – it’s the doing and not the done.

Gerry is a maker through and through, who can blend the personal and the private, high and low art, with enough technique to make it work but not too much that it becomes inaccessible, cut off from daily life. If Dylan is criticized for appropriating content then Gerry absolutely revels in re-using and reinventing the images that soak our daily lives; images that, even if we don’t necessarily want them to, inform our histories.

His 2016 Henry Lee Pot, based on Nick Cave’s rendition of the ballad ‘Henry Lee’, addresses various plot themes in different versions of the song, which has previously been called ‘Young Hunting’, ‘Poor Henry’, ‘Love Henry’, ‘Earl Richard’, ‘The Proud Girl’ etc., etc., etc. Gerry says he draws on the ‘narrative aspect of folk music and its potential for constant revision and reconfiguration’ as well as referencing the actual illustrations from material like old record covers and magazines. In addition, he often uses a pictorial device where this imagery is deliberately drawn in a manner that suggests a crude woodcut or linocut, whereas of course it’s nothing of the sort.

We think of this borrowing as being modern, the result (firstly) of the recording arts – photography, then film and sound – and then of post-modernism, but ceramics has a long history of appropriation. The Istoriato painters of sixteenth-century Italy wandered the Umbrian countryside as journeyman ceramic’s decorators, copying imagery from the woodcuts that were taken from paintings and deftly applying it to faience wares.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time watching Gerry work as a decorator and he has the ability to do what those Istoriato painters did; mixing invention with repetition, drawing on an enormous vocabulary of fragments gleaned from a bewildering variety of sources, turning out the work, making dreadful puns (“thong cycle” anyone?) and listening to music - always listening to music.

In Gerry’s ceramics the dark shadows of colonial history are balanced by the twang of guitars and the glitter of sun on the surf. There’s salt and frangipani, humility and humanity, the feel of sand between your toes and the hint of blood in the water.

I’m lucky to have seen some of the major works, in this exhibition of Gerry’s, being made in the studio at the JamFactory, and I even own a couple of the minor ones, which I’ll get to enjoy one day - after they finish being on the road.

Damon Moon

Adelaide 2017

'Liz Williams - the Figure in Clay' in Body Language published by Wakefield Press 2017

Liz Williams: the figure in clay

This is an edited version of an article originally published in Ceramics, Art and Perception, issue 73 in 2008

The history of figurative sculpture in ceramics is marked both by its antiquity and the inherent limitations of the material.

Clay has always had the advantage of being malleable, abundant and virtually free, but it also has distinct drawbacks when used for sculptural purposes. Clay must be kept moist in order to be modelled but moist clay has limited mechanical strength. This can be somewhat compensated for by making the pieces thicker – and consequently heavier – but this thickness then becomes a problem if the piece is to be successfully fired, as the moisture contained in the clay has to be driven off slowly as the water turns to steam, but if the clay is not fires then it is nothing but dried mud, and so it goes. Put simply, making large sculptures out of clay is not the easiest thing to do.

Different cultures have found different solutions to these challenges. The apotheosis of archaic figurative ceramic sculpture is found in the so-called terracotta warriors ( in pinyin bingma yong or ‘soldier and horses funerary statues’), a collection of around 7000 life-size warriors, together with horses and chariots, that were made during the reign of the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang around 200BC.

As with all Chinese ceramics, an astonishing level or artistry was achieved through long familiarity with the material combined with a no-nonsense approach to manufacture that was more akin to industry to art. It is salutary to remember that Chinese ceramics, be they a terracotta warrior or a Sung bowl, reached dizzying aesthetic heights through a collective approach to making art that is antithetical to our contemporary notions of how art is made and the importance we place on individual expression.

Inspired by another Chinese ceramic tradition, that of porcelain, European manufacturers have since the early 18th century produced vast numbers of ceramic figures which combine an exquisite control of clay and glaze with imagery taken (albeit in a degraded form) from neo-classical traditions. The consequences of using that most difficult of ceramic materials – porcelain – to mimic a formal language grounded in the obdurate necessities of craved stone or the unfettered language of paint was that the scale of the porcelain figure was severely constrained.

What may have started life as an imposing figure occupying a central place in an Italian piazza was reduced to a bibelot sitting on a square foot of polished-timber dining table: where Neptune once raised his trident over splashing fountains and pulchritudinous mermaids, he now lorded it over the halibut.

It is debatable just which of these two traditions has had a stronger influence on modern figurative ceramic sculpture, but there certainly were places and times in this country where the delicate and rather effete quality of Dresden centrepieces took the upper hand, not the least being Adelaide in the 1970s where the precursor to what was later termed Skangaroovian Funk lived uneasily beside a curious amalgam of Japanese-derived folk traditions and English rural pottery that constituted the Anglo-Oriental tradition of studio pottery.

All of which makes Liz Williams work more remarkable, since she instead developed a language which finds its grammar in the hieratic, totemic and folk traditions of ceramic sculpture, rather than the florid and gilded excesses of the China cabinet. Just how this came about makes for an interesting story.

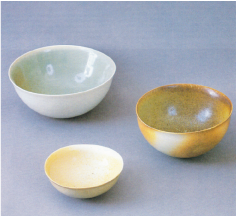

Williams has been making ceramics for forty or more years and she is certainly well-trained, although her sculptural work reveals no direct influences from Milton Moon, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott or Paul Soldner, teachers she had direct contact with during the 1970s and early 1980s. Her formal education encompassed both the Anglo-Oriental tradition of functional pottery (the celadon bowls which kept reappearing throughout her working life were markers of a tradition she honoured, even if her artistic output took a very different form) and the experimental approaches of Californian ceramics, all of this during a period when ceramics was arguably enjoying its most diverse and rambunctious phase.

Williams was among the first generation of ceramic artists trained in this country where everything – information, publications, techniques, materials and styles – suddenly became available. It was simply all there for the taking. Faced with this confusion of riches, Williams did the sensible thing: she began to work through her artistic options.

Her early work was not strident but neither was it shy. She moved from functional stoneware to raku, gradually altering the vessel form and experimenting with decorative techniques.

In Los Angeles she worked with Paul Soldner at Scripps College and she often travelled to San Francisco, looking long and hard at the Avery Brundage Collection, one of the world’s great collections of Asian art, then housed in a wing of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in Golden Gate Park.

She became fascinated by the relationship of Chinese ceramics with bronzes, and her work at this time shows the influence of formal and decorative devices sourced from these archaic works, successfully translated into a contemporary, personal idiom. Although this work would not provide Williams with her mature artistic destination, it demonstrated an increasing ability to interpret, a facility which would stand her in good stead.

When tracing the development of her current work – these still, carefully modelled and rather reductive figures – one searches for the moment where the decorated vessel finally transited into the unadorned, sculpted figure: where glaze and colour gave way to plain clay and the subtleties of posture. None of this happens suddenly, over the course of a day or even a year, but looking back it is often possible to identify a time or place which seems to provide the necessary impetus for a profound change to occur.

In 1993, as part of the national Ceramics Conference held in Adelaide, Liz Williams held an exhibition of figurative ceramics at the Adelaide Central School of Art Gallery. Titled Recuerdos (which may be translated as meaning memories, memorabilia or even remembrances) this work called on experiences she had accumulated during a study tour of the US and Mexico in 1991. Groups of clay figures were lit by candles, at once evoking a church and a reliquary, Spanish Catholicism and the rich tradition of pre-Columbian America.

In modern parlance, it was an installation. It was a pivotal moment in Williams’ development, one where she publicly declared her own thoughts in a language she then refined for the next twenty-five years.

The changes to her work over this time have been incremental, thoughtful and restrained. The basic elements have remained the same, but there have been a myriad of subtle shifts. One of the most notable differences has been an increasing realism, a fidelity, born of Williams’ involvement in teaching and her observation of the movement (and occasional stillness) of children. The coltish pose of the young ballet student, the distracted expression of a youngster occupied with their own world, all of these things have been observed and noted to re-emerge in clay.

At times, there is an air of theatricality to the work, in the use of props like a bright red chair, an earring or a mirror. But, more and more, the emphasis is on the body, at rest and in motion, and in pushing the technical limits of clay to keep up with her demands.

This is made all the more complex when the figure is required to stand without external support, because Williams’ figures stand as we do. This provokes a sort of kinaesthetic exchange between the viewer and the viewed (that most under-explored topic of art theory) where we somehow intuit the fact that these figures are not pinned, fixed or glued to the ground, and that their stance relies a little, as we all do, on trust.

Williams’ constant challenge is to fulfil this need for balance without the poses becoming stuff and constrained. Her solution has been to invest the figures with a certain abstract quality whereby they are not realistic enough that we expect them to be fully animated, but by deferring to small gestures – the bunny-rabbit shoes worn by a young dancer – they mark us as human. After all, the aim of the work is not verisimilitude but empathy, or perhaps she would have said simpatico.

There are other discrete references to be found; the tutu made of real cloth worn by Edgar Degas’s famous 1880 bronze La Petite Danseuse de Quartorze Ans is certainly there and the curious, pear-shaped figure that comes directly from the 15th century Northern-European painter Lucas Cranach the Elder. Contemporary work is also quoted, with Williams’ friend, the painter Gary Shead being directly referenced and one might easily think about the work of Charles Blackman, at least in the subject matter.

But these contemporary resonances seem always to be balanced (there’s that word again) with a much older tradition found in the anonymous works of pre-Columbian America, of China and in the folk traditions of Christendom.

During the last phase of her career, following her retirement from full-time teaching, Williams’ output increased. An inveterate traveller, she constantly informed her practice with observation of the contemporary and the art of the past, with her last prolonged residency in Japan leading to yet more refinements to her oeuvre. There now will be no more quiet figures, but those that remain stand in testimony to a life well-lived. They will, of course, outlive us all – for that is the nature of clay.

Damon Moon

Adelaide 2017.

Liz Williams, Body Language, Wakefield Press 2017

Exhibition Review

Already seen in Vietnam and scheduled to be exhibited in Singapore from 19 April to 7 May 2007, Stephen Bowers, the curator of A Secret History of Blue and White, contrasts work from five Australian ceramic artists — Stephen Benwell, Robin Best, Bronwyn Kemp, Vipoo Srivalasa and Gerry Wedd — with that great body of objects, spanning time and cultures, which constitute the legacy of blue and white ceramics.

A collaborative project between the Asialink Centre of the University of Melbourne and South Australia's Jam Factory Contemporary Craft and Design centre, exporting contemporary blue and white ceramics to Asia might fairly be seen as sending coals to Newcastle. Indeed, although having its origins in China, the cultural memory triggered by the term 'blue and white' could well be voiced in that Staffordshire dialect peculiar to 'the Potteries'; a cloth-capped and heavy-forearmed sort of accent, reified in the shards uncovered periodically in back yards all over Australia. These transfer printed fragments of Empire are still with us, and it is to this casual archaeology that the Adelaide-based Robin Best and Gerry Wedd return. Wedd's 'Willow pattern' ceramic thongs are a daggy foil to Best's china, both relying on irony as much as cobalt to make their point.

Originally from Thailand and now working in Melbourne, Vipoo Srivilasa posits the history of 'Lai Krarm', a Thai term for pottery with indigo designs, as his starting point in a process of cultural exchange. By contrast, Stephen Benwell continues his painterly dialogue with clay, while exploring a brusque figuration in ceramic sculptures. Of the five artists, Benwell seems less concerned with commenting on specific ceramic histories, instead relying on the qualities inherent in this time-honoured chromatic combination. Bronwyn Kemp's ceramics simultaneously evoke the topographical and seismological mapping of the landscape, a testament to her background in the evocatively named mining town of Broken Hill.

The exhibition is accompanied by a useful catalogue essay by Bowers. It would seem that the secret is out.

Damon Moon

'Ansate' published in 'Garland' magazine, 2016

Ansate: Having a handle or a part resembling a handle.

Sorry. I’ve begun this essay with a definition of an obscure word. Don’t you hate that?

When Kevin Murray and I were having a coffee during his visit to Adelaide in December of 2015, he was musing (as only Kevin can) about the presence or absence of handles on ceramics. We talked a little about their history, their use, their cultural associations and all the while I was trying to remember a word I had heard only a couple of days before, a word used to describe both a handle and object that possessed a handle. Kevin was keen on teasing out the metaphoric possibilities of handles and how that might find its way into a discussion of the state of contemporary ceramics, and this seemed like an interesting idea, especially considering I’d heard that word …. well, that word I couldn’t remember. It came to me after he left, of course. Ansate.

I do like the idea of ceramics being handled, at least in the sense that they are used, but as someone who runs a production workshop the presence or absence of an actual, as opposed to a metaphoric, handle is both a matter of design and of economics. A handle adds time to the process of making and time is money. A hand-thrown teacup and saucer is a surprisingly expensive item to make, and as for a teapot! A teapot has a body, a lid, a spout and a handle – very complicated, very time-consuming. This might be the reason that many people are keen on making tea-bowls, and they do have the advantage of being satisfying and relatively easy to make, at least in terms of the technique involved. Having said that, I never use tea bowls to drink tea, although I do love making them and they come in handy for peanuts. Even the Japanese normally don’t drink tea from a tea-bowl, despite these objects being held up as the be all and end all of Oriental ceramics. The Japanese usually drink tea from a beaker without a handle, waiting until it is cool enough to hold. I drink coffee from a beaker, because coffee is rarely that hot, but for tea I use a cup or a mug, with a handle, because I like black tea (red tea, actually – Rooibos), and tea without milk makes the cup really hot.

Handles are for heat and sometimes for leverage, as with a jug, but a jug only needs a handle when the vessel becomes too big to be grasped by the hand, when it becomes ansate. Phew, glad we got that lot out of the way!

The only reason that I know what this word ‘ansate’ means is because, a few days before I had coffee with Kevin, my wife and I were sitting down after work and she was entertaining us by reading out some obscure words from a splendid old American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.

It’s a lovely book with red covers and gold edges, a cross between an encyclopedia and a dictionary, with lots of little drawings and photographs in the margins. Considering how long she’s had the book it’s in remarkably good condition, although it does have a matching box, which helps keep it safe. This book has moved with us to many houses (it moved again just a couple of months ago) and it has always been looked after, but it is also well made, a fine example of the book-binders craft.

And, being a book, I can tell you that the listing for ansate is directly followed by ‘ansate cross’, which is a cross with a loop on top, sometimes called an ankh; Anschluss, the political union of Austria and Germany in 1938, which obviously was not a good thing; Anslem, the name of a Saint who was Archbishop of Cantebury from 1093 to 1109; and, my favourite, anserine, meaning goose-like.

A book is always ‘handled’ if it is to be read, so it lends itself to this sort of information gathering. As I’m reading the definition of ansate I can’t help but see these other words. They are within my field of vision, within my ocular grasp. I can get a handle on it all.

In this world full of distant instants there has been a heartening reawakening of an interest in hand-making and the hand-made – it even has its own name now, the ‘makers’ movement’.

Whether this has come about as a reaction to the plethora of images that surround us and the speed by which they’re transmitted, or through a need to supply a form of content that shows there is a person behind the post (a sense of selfie?), the new digital seems to have reinforced the old digital, those waggly things on the end of our wrists.

Whereas the intellectual obfuscation surrounding post-modernism stifled an interest in ‘doing’ (very hard to do something if no one is sure if anything has any value), social media has led to a culture of ‘sharing’. This new kind of sharing is very convenient, in that you don’t actually have to relinquish a portion of something that is yours and give it to someone else, to hand anything over; rather, you simply let them look at something. It is the sharing of information, not of goods, but the object is still central to the equation, as is evidenced by the many sites where people digitally curate the hand-made.

The culture of sharing goes hand in hand with a return to making. Even amongst those who aspire to the avant garde, the post-post-modernists, where the notion of deconstruction (de-skilling is now in fashion) still holds sway, there is a fad for making, which probably explains the proliferation of ‘bad ceramics’ invading high-end galleries. Wonky pots are the new video, as I’m sure you’ve heard, and Grayson Perry is beginning to look a lot like Bernard Leach. These are the pots-modernists.

At the more democratic end of things, where tastes are less corrupted by an excess of excess, the return of the general public to classes and workshops, where they can learn about making, has been quite extraordinary. Not unprecedented, because there have been times in recent history where involvement in the crafts has been equally strong and maybe even stronger, but this latest resurgence is taking place without much government support. It’s crowd-funded, which is another way of saying that people are spending their own money to make something happen.

In my role as Creative Director of Ceramics at the Jam Factory I get to see it all, from working with practitioners at the highest level to training recent graduates who want to transition to professional practice, as well as running night classes for the general public, and I find it very encouraging that when I look at all of these spheres of activity they seem to be going from strength to strength.

If that means that every night class we run at the Jam Factory is full – which they are - and that all the other organizations I’m aware of are having the same level of success – which they are - then that’s great. That’s a sign that the craft ecosystem is healthy, that there’s diversity and numbers, that the rivers are flowing and the rain is falling.

There are, of course, still some problems, especially in the tertiary sector, where the range of skills has been diminished, because classes are attenuated and teachers are expected to do ever more with ever less. Current graduates coming out of a three year course are trained to the level first or second year students used to be. But that’s OK, as long as the numbers are there and other individuals and organizations are able to take up the slack. In a way, what’s happening now looks a lot like the late 1950s and early 1960s, where a smallish tertiary sector sits alongside the option of private tuition feeding a rapidly expanding sector of small manufacturers, thanks in no small measure to on-line sales platforms and the popularity of craft markets, as well as more traditional bricks and mortar shopfronts. It is a very interesting time to be involved in the crafts and it is, on the whole, a hopeful time. It just needs to be handled in the right way.

Damon Moon, Norwood

December 2015

Susan Frost

In her memoir Taken from the Back Row, Cosmopolitan.com editor Amy Odell describes being interviewed for a position as a fashion writer by the somewhat terrifying personage of Vogue's legendary editor, Anna Wintour.

Searching around for tips, Odell was informed that Wintour was 'all about colour', and so whatever she did she should avoid wearing black. In the end she chose to wear a cream dress and 'nude pumps', surely a term to conjure with. She didn't get the job, a career glitch which she puts down to getting almost all her answers to Wintour's questions wrong, but one has to wonder if the choice of a cream dress had anything to do with it. After all, nothing's that black and white.

Colour in ceramics has similarly been subject to fashions, as well as being dictated by technology throughout its long history. Who hasn't heard the term 'brown pots' being used somewhat disparagingly, although now the worm has turned, and brown is the new black. Studio pottery has seen various palettes come and go - Clarice Cliff, Grace Crowleyand Memphis were pretty gaudy, there was blue and there was white, and recently there was a period where everything white huddled together, perhaps an unwitting metaphor for contemporary politics. Colour can be a serious business.

By contrast, I would say that Susan Frost's work plays with colour, if play can indeed be this careful and considered. Taking her cues from various sources, including the faded hues of old Polaroids, and matching these to simple, domestic forms, she manages to achieve what seems to be limitless variations on a theme, with perfectly applied colour over perfectly formed Southern Ice. Her ceramics are at once contemporary and nostalgic, and one could imagine a photo shoot featuring picnic blankets and green grass and wicker baskets, especially if the photo was manipulated to mimic the old dye-transfer techniques. I drink my tea from one of Susan's cups every day. Its pale yellow and quite flawless, although according to Susan it's a second. Then again, she would say that, wouldn't she.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2015

Simple Virtues 'The Art of Function, the Function of Art'

In the early 2000s I was coming to the end of a curatorial project which involved chaperoning an international touring exhibition of contemporary Indonesian art around Australia. I had spent the last few years going to and from Indonesia, initially on an Asialink residency, researching, raising funds, and generally just doing whatever it took to get 'AWAS! Contemporary Art from Indonesia' seen by an audience in Australia, and subsequently in Japan, Germany and the Netherlands. AWAS! was a great show and well worth the effort but by the time it arrived at its final Australian destination at the Cairns Regional Gallery I'd had enough. On the first day in Cairns I did my back in trying to move a crate in the loading bay and for the next week I supervised the install, attended the opening and conducted the floor talks in considerable discomfort. Arriving back home in Adelaide I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that I needed to relax, stop travelling as much and get back to basics, which for me has always been ceramics. It was also a period where a bit of self-reflection was in order, as the years I'd spent working with contemporary art had shown me that it was not a world I wanted to be immersed in as a permanent career.

Since I didn't feel ready to jump straight back into full-time making I decided to do a PhD in art history, looking at aspects of the development of Australian ceramics in the post war period. This was also a way of trying to make sense of my family history, to examine and order the experiences, people and images that had made up my childhood and see how they could be situated within the wider history of the crafts.

What could be easier, I thought? Lots of reading, a bit of writing (well, actually a couple of hundred thousand words of writing ending up as an eighty thousand word thesis with a thousand footnotes) three years of a university stipend - my God, I'd be so relaxed I could barely keep my eyes open.

Hmmmmm .......

Anyway, in the lead up to all of this, and despite the fact that I wanted to do the PhD purely by thesis, I began, in a very low-key manner, to make some pots. There were a few reasons for this, one being that my forays into the world of contemporary art had left me missing the simple act of making, and I do like making. Secondly, I began to explore the use of local materials in making functional work, as this philosophy was a part of the Leach/Cardew and subsequently McMeekin et al approach and this was something that informed my PhD research. It proved to be quite fascinating, and it was somewhat of a revelation to find out that that one could go for a drive in the hills with a pick and shovel and some empty buckets and sacks and collect useful, lovely materials with which you could make pots. Friendships were made with people that owned quarries, maps were marked with the locations of mineral deposits and wood ashes were sourced from different plants. It was like having a lovely hobby and the results - after several false starts - began to be worth the considerable effort this way of working entails.

Around this time I was contacted by the well-known chef and author Gay Bilson, who had just moved to South Australia after a high profile career in New South Wales, where she had variously run the restaurant at the Sydney Opera House and the famous Berowra Waters on the Hawkesbury River, a restaurant so exclusive that one had to access it either by boat or make a rather spectacular entrance by seaplane - as you do.

Gay was in Adelaide to work with the avant-garde American theatre director Peter Sellars, who had been appointed director of the 2002 Adelaide Festival of the Arts. Sellars, an eccentric figure who looked for all the world like a character out of an early David Lynch film, had promised a festival that would truly live up to the rhetoric of being cutting edge, innovative and challenging. Much to the concern of all involved it rapidly became apparent that he wasn't just saying this would be a festival like no other, but that he actually MEANT it. Sellars would eventually resign a few months before the festival opened leaving a large hole in the budget and a sort of anarchic cultural echo which has the effect of rendering every subsequent festival more predictable than the last, not that anybody notices in the midst of pop-up hipster venues and thousands of dreadful Fringe comedians.

As part of Sellar's proposed program food would play an important part in the proceedings, with a mix of events from gastronomic symposiums (rather like writer's week but with balsamic drizzle) to conceptual projects exploring the intersections of food and society. Gay - another person who definitely doesn't conform to expectations - came up with a project whereby she would supervise some meals for patients at local hospitals. She was looking for a potter to make work for several of these events and she ended up with me.

Two sets of work were finally made. Some plates for a symposium dinner and a couple of hundred small bowls for the hospital project and in the process of making these things I found a renewed passion for the functional, the simple, and the real. Not art, not 'Ceramics' with its capital C, just bowls and plates for food. Simple enough, or maybe not.

Jump forward thirteen years and I'm working as Creative Director of the Ceramics Studio at the JamFactory in Adelaide, where 2014 ended with us having made at least three thousand items for local restaurants and the domestic table. These were based on our 'Thrown' product range (featured in JAC Vol. 53 No. 3 November 2014 pages 78, 79) designed in house and made by local craftspeople in the JamFactory studios from local clays made by a local company and not, I repeat not, 'Made in China'.

In addition to all this activity, there has been one commission that I have been working on myself out of the Jam studios, for Scott Huggins and Emma McCaskill, the executive chefs at the Penfold's Magill Estate Restaurant, and it is this work that I want to end this article by discussing. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that they spent time working in Japan, where they were exposed to the the myriad aspects of Japanese ceramics, a far cry from the ubiquitous white-ware which 'plates up' so much Australian food. And there is also an element of fashion, where adventurous restaurants and cafes are more and more wanting to have individual, bespoke ceramics to match their food. There is also the fact that Scott and Emma, like many other chefs, are interested in the local, the seasonal and the variable, they want their ceramics to reflect this and by working with a potter they have the chance to explore textures, shapes and colours designed to really compliment the food.

Over the year, fitting it in with my other responsibilities and having more than a few failures along the way, I have been slowly making and supplying Magill Estate with nine sets each of thirty items for their degustation menu that are quite unlike any 'normal' white wares, and some of which might even push the boundaries of what is expected of hand-made ceramics for the kitchen or table. Using the ash from their kitchen braziers where they burn the pruning offcuts from Penfold's vineyards, to utilising hand dug kaolins which, when un-sieved, still contain feldspar and quartz inclusions, to plastic black, sodic clays gathered from the vineyards and olive groves that surround the little town where I live, I have tried to make work for them that is absolutely suited to their needs whilst truly reflecting the landscape, because it is from the landscape. I think we have similar aspirations, Scott and Emma and I, albeit in different fields, and I hope that the relationship will be ongoing, because nothing delights me so much as when they unexpectedly send through an image of food they have arranged on one of my - their - plates or dishes or bowls, so making it complete.

Honestly, who needs art?

Damon Moon

Willunga 2014

Published in the Journal of Australian ceramics Vol. 54 # 1 2015

Some comments on the work of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott

An address given at the Art Gallery of South Australia on the 15th of September 2013.

It seems that we have lost some wonderful women from the ceramics world of late. So much of the early history of ceramics as part of the craft movement in Australia is about women — as makers but also as editors and gallery owners and teachers and organisers. The blokes often got the lions share of attention, and a lot of the top jobs, but Gwyn ended her innings at the very top. She did what no one else had done before, and good on her.

In the process of writing about Gwyn for the next issue of the Journal of Australian Ceramics – and they are publishing a much larger article than usual, which is only right and proper - I came across some archival material that might serve as a good starting point for some observations about her life as a potter.

Some time ago Susie McMeekin gave me copies of correspondence between her father, Ivan McMeekin, who was Gywn’s first teacher, and Bernard Leach. The letters are mainly to do with Leach’s visit to Australia and New Zealand in the early sixties, since McMeekin was instrumental in organising Leach’s itinerary during the few days he spent in Sydney. They are lovely documents — a couple of aerogrammes, which Susie had thoughtfully copied in colour for me so the original blue colour of that fine paper was preserved — and a letter. Some are typed and others are written in Leach’s distinctive hand-writing.

Apart from anything else, these modest documents remind us of how those involved in the ceramics world were a well-travelled lot. Especially Leach - one of the letters outlines his flights as he travelled between Wellington and Sydney, en-route to Tokyo.

In these letters Leach talks about Gwyn, as she provided a continuing connection between the English pottery world and Ivan McMeekin, between Australia and Britain. There were others in this lineage of Australian potters who had studied in England – Marea Gazzard was in London at the same time as Gwyn, David and Hermia Boyd had worked in England and France in the fifties, McMeekin had been there in the late forties and fifties, and Gladys Reynell, Margaret Preston and Norah Godlee were all there before the war.

In a letter dated the 30th December 1959 Leach expresses a kind of fatherly concern for Gwyn’s emotional welfare, observing that her ‘ … affairs of the heart have rather thrown us all for a loop’. You get a lovely and very human picture of a young woman who is finding her way in the world but is already very much a part of a community, and I think especially in those days the ceramics world really did consider itself a community.

Another letter from Leach is dated the 18th May 1962. The stationary it’s written on was from International House in Tokyo, but this is crossed out and over it Leach has written 18 Albion Mews, W2, care of Lucie Rie. He writes that ‘ … Gwyn and Louis are having a show at Primavera and Lucie gives a fine report of their pots.’

Just by chance I happen to have a 1962 copy of the English journal Pottery Quarterly where the Primavera show is reviewed — it notes that Gwyn ‘ … is a potter’s potter …’ and that her work more or less summarises the ‘Leach-Cardew-Davis-Finch field, and in this respect is akin to the work of the Mackenzies in the USA and McMeekin in Australia.’

There is a photo of her work in the magazine, of a punch bowl and ladle with six cups; a quiet stoneware setting, now almost a craft cliché like goblets of ramekins, but then very much in vogue.

She was twenty-seven years old and already pretty well regarded. The review also mentions that although she came from Australia with, and I quote — ‘far-away-Commonwealth-shining-bright-images’ - she quickly settled in to the realities of the British ceramics scene. So much so that she came to be regarded as a British potter. Even when she started to spend much of her time in France she was included in exhibitions like More British Potters – which is from the very late sixties or early seventies, although the catalogue doesn’t actually have any dates listed, which drives me absolutely mad, but I digress. Here, the work she made in France is included with ceramics from Bernard and Janet Leach, Lucie Rie, Michael Cardew, Hans Coper, Ruth Duckworth, Ray Finch, Marianne de Trey and Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie – she kept good company.

But she was also aware of the paradoxes presented by the life of a potter, especially when she was involved in trying to make very traditional, useful pottery, as she was doing in France. In 1969 she wrote that … ‘ we younger potters can never be potters of Haut-Berry and we can never recapture the spirit that has passed. We remain our immigrant selves, alone always, our work our own personal struggle and delight.’

The line ‘our immigrant selves’ is memorable — as a writer it’s the sort of line which makes you think ‘Oh, I wish I’d written that.’

She later recalled that she had … ‘tried to make something which would be real. I hoped that if I lived like a traditional potter somehow I would make pots like those unpretentious craftsmen in times gone by. But in fact I wasn’t unpretentious at all — nor simple … I was acting a part that I hadn’t the strength for, and I was caught in a very subtle ambition to which I saw no end.’

But there was an end, and in 1973 she returned to Australia, although she was to all intents and purposes a British potter.

Of course it’s difficult — and arguably not very constructive — to stereotype these things, but just as Margaret Dodd came to pottery in California in the 60s and has basically remained a West Coast ceramist ever since, and just as so many Australian potters were incredibly influenced by Japan, to the extent that they spent their lives making copies of Japanese pots, to me Gwyn was always an English potter.

A bit cool, distanced maybe, controlled, polite, the work quite small in scale, very considered, beautifully crafted, thoughtful.

She spent the next fifteen or so years making lovely, understated pottery at a time when the volume of ceramics was turned up to eleven. Funk, pop, expressionist sculpture, Memphis – the maker of domestic ware didn’t get much of a look in. It was simply not a very fashionable thing to be doing. If Gwyn had remained a competent maker of lovely useful pots at a time when the ceramics world was clamouring for — well, often just clamouring, really — she wouldn’t have become the enormously successful ceramic artist that she was.

But something changed.

The work she is famous for, the groupings that had their beginnings in the late 80s when she was with the Gary Anderson Gallery and that developed over a period of a few years until she had sorted out their dynamics, were in some ways a continuation of her earlier work. But in other important ways this work was completely different to what had come before, and it is as a result of those differences that we are here today.

The common thesis is that her original groupings quickly morphed into arrangements of objects that borrowed heavily from Morandi and these works are now even called still-lifes, a proposition which is both right and wrong.

Here is a quote from Robert Hughes about Morandi.

‘Instead, the things … seep deliberately into one’s attentions. They start vaguely, as little more than silhouettes, a vibration of one low colour against another. Gradually, they ‘develop’ on the eye, and one begins to grasp their internal relationships: how articulate the subtle sequence of tones may be … how many colours may be contained, as dusty hints and pearly afterimages of themselves … If the straight side of a bottle seems to waver, it does so only to remind us how mutable and hard to fix the act of seeing really is. And if the shapes look simple, their simplicity is extremely deceptive; one recognises in it the distillation of an intensely pure sensibility, under whose gaze the … the silence of the motif and the inwardness of vision are one.’

Remind you of anyone?

The problem — or should I say challenge — is that Gwyn’s work isn’t really like Morandi’s at all, in that Morandi only used the collection of little bottles and vases sitting before him as a starting point — they weren’t the end product. I used to have a picture of Morandi’s studio with the objects he painted sitting on a table, and the scene didn’t resemble a Morandi painting at all, so in that sense he certainly wasn’t a still life painter after the traditional Netherlandish or Spanish school, where a microscopic attention to detail was matched by the rich allegorical messages contained within the works. Morandi was just this side of abstraction and his paintings didn’t say much at all — he was just obsessed with shapes and colours and the limitless manipulation of form within strict boundaries. To the extent that Gwyn was influenced by Morandi she did exactly the same thing as he had done but in reverse — she extracted the core idea from his painterly interpretation of real objects and then applied it to back onto studio pottery.

This raises the question of just what Gwyn’s arrangements were, and my answer to this question would be — in the first place — that they were both very simple and very complex, and that is their allure.

They exist somewhere between art, craft, curatorial practice and interior design, and they are both the object and its depiction at one and the same time, which, when you think about it, is quite a trick. In fact, whereas Morandi is quite the modernist one could argue that Gwyn’s work is essentially post-modern (which I just mis-typed as pots-modern ,,,,,) – in that it slips between pre-existing categories and refuses to be pinned down.

Her work is also very self-aware, in that it engages with the mechanisms of context and display at a highly sophisticated level. To this extent it is akin to some ephemeral contemporary art that relies heavily on context to activate its relationship with the viewer, but it does so much more tidily than a Joseph Beuys pile of felt sitting in the corner of a contemporary art space. You can invite Gwyn’s pots home in the full expectation that they will perform the same function in your living room as they did in the gallery, and if hard pressed they can probably do a job in the kitchen as well.

The thing I find most interesting about Gwyn’s work is that it champions the causes of technique, beauty, calm and poise, in a time when contemporary practice is seemingly completely biased towards shock and awe, parody and discomfort. That it proved to be so successful is a lesson in itself.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2013

Afterword

As a historian it’s sometimes difficult to decide what information should remain private and what should be noted when giving an account of an artists career or working life, which is a part of - but not the entirety - of their life.

In the case of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott there is one factor which is both personal and yet had a great - even an overriding - impact on her life, and that is her unwavering devotion to a spiritual movement centred on the teachings of a young Indian mystic or guru named (then) Maharaji.

Margaret Tuckson, in her article on Hanssen Pigott for Pottery in Australia Vol.22 No. 2 quotes Hanssen Pigott as saying that .’.. In late 1972 I was told about Maharaji and went to a meeting in Paris to hear more. I remember feeling a secret excitement. It was obvious to me that these people were speaking from a real experience and clearly if what they were saying was true I had to know the experience for myself. I felt such a relief. I was tired of theories and philosophies and impossible romanticism. I set off to find one of Maharaji’s appointed teachers and a few days later in London I was shown such a beautiful energy inside myself and an experience of peace that took me by surprise and changed everything for me. It was Guy Fawkes night in London and I felt that all the fireworks were celebrating with me.’

What is largely unstated in all the existing tributes to Hanssen Pigott is that from that moment on her devotion to the Maharaji (which those who knew her intimately sometimes disparagingly refer to as ‘The Cause’ controlled most aspects of her life. Her decision to leave France (the pottery she owned became an ashram) and her movements within Australia were largely dictated by the needs of ‘The Cause’. Her relationships suffered and many who knew her would observe that her devotion to the Maharaji did not necessarily bring her peace or tranquillity.

It will be for others to examine this aspect of her life more closely if a biography of her life is ever undertaken. In terms of art history it is necessary to mention, if only in passing, this side of her life, in that it explains many of the sudden and rather unexpected shifts in location, which in turn impacted on her career.

Damon Moon

Willunga, August 2014

Filthy Lucre: how money has helped to shape Australian ceramics over the past half century

“The best things in life are free

But you can keep them for the birds and bees Now gimme money (that’s what I want) ”

Nostalgia can be comforting, but it’s all too easy to wallow in a past that was really more like the present than one likes to think.

The Gordy/Bradford song was playing around the time Pottery in Australia was first published in 1962; Robert Menzies was Prime Minister, and EK Holdens were rolling off the production line, and tended to (forgive the tortured metaphor) paint a picture of Australian ceramics in, if not sepia tones, then at least colours reminiscent of an old Kodachrome slide. We think of it as being far removed from what happens now, but the reality is that only a few changes have occurred in Australian ceramics over the past five decades, and those changes, important though they are, are probably not the ones we expect to find.

For a start, not a lot has altered in the sort of work that is made. Ceramics can still be separated into the same categories of objects that it occupied fifty years ago; namely, vessel-based work and everything else. There may be a quibble about when ceramics becomes sculpture or at what point a pot becomes

a representation of a pot, but, for the purposes of this discussion, I’m contending that nothing new has arrived on the scene during the past half century.

We’ve had faux Sung and faux just about everything Japanese, Modernism, Funk, Memphis, Post Modernism, Cool Porcelain, Designer Groupings, Conceptual Clay and God knows what else. Even the seemingly recent innovation of installations date back at least to the mid-seventies.1 Some styles seem to have come and gone while others have endured, but perhaps the only really notable change in all that time has been a shift in interest away from brown clay, once the staple of Australian potters, to the almost universal use of white clays, particularly porcelain.

This preference for etiolation also touches on the question of techniques and materials, but again very little has actually changed. Earthenware pottery, once the mainstay of early Australian studio pottery, made quite a comeback in the 1970s and 80s, while the fetish for porcelain has continued to grow, making the wide brown land into the great Southern Ice-land. Although the use of more ‘natural’ materials has diminished, the woodfirers still show a significant commitment to a ‘back-to-nature’ approach, even if that means utilising pre-packaged and specially formulated clay that will react nicely to a three-day firing in an anagama. (And just trying to say “in an anagama” surely deserves some sort of prize.)

Shifting our attention to how ceramics is taught, it seems that here at least there have been some significant shifts, with the precipitous decline of ceramics as a discrete subject within the art curriculum being the most radical change of all. Nonetheless, what has remained constant is that the teaching of ceramics to adults has mainly been undertaken by tertiary institutions as part of the ‘higher education’ sector – bodies funded by the government that award qualifications of various sorts.

An unexpected consequence of this situation has been the proliferation of ceramicists who now possess higher degrees, but this says more about the way art schools have been incorporated into the university sector than it does about the work that is made. Universities are funded to do research and they take every opportunity to frame their activities within these guidelines, so if an art school is part of a university it is only reasonable to expect that some students will take matters to a logical academic conclusion.

There are several other possible approaches as to how ceramics might have been taught, but few of these met with any success. Despite some valiant attempts to set up government-funded apprenticeships, this approach never caught on, and privately funded apprenticeships were always destined to fail in a country where the teacher could hardly earn enough from the sales of work to support themselves, let alone a trainee. The other approach, where ceramics was taught as a genuine trade, wasn’t ever really a starter, since traditional ceramics manufacturers were dying out by the time the post war crafts movement had taken hold.

Despite this reliance on the art school system, the position of ceramics within the marketplace has always been more ambiguous, with goods appearing in venues ranging from high-end galleries to craft shops, private showrooms and even stalls in local markets. Sometimes a ceramicist would place work in all of these venues simultaneously, showing a promiscuous disregard for the niceties that constrained more mainstream artists and helped defined their practice.

Maybe the only consistent factor in Australian ceramics has been its continuing marginality; always one sandwich short of a picnic as far as the art world was concerned, and increasingly fated to be on the decline with a general public spoiled for choice in a modern consumer paradise. In fact, it is this last observation which points to the factor that has conditioned every aspect of the development of Australian ceramics, from the amateur to the professional, from academia to the marketplace, in both the public and private sectors, and that is money.

Money may indeed be the root of all evil2 (actually this is a malapropism – the original quote suggests that the love of money is the problem) but the economy of the crafts, how money is earned and distributed within a community of makers and consumers, has shaped Australian clay as surely as the hands of a skilled craftsperson.

To see how this has happened, we must go back to the late 1940s when legions of returned servicemen, aided by government funded retraining schemes, enrolled in courses in art schools and technical colleges throughout the country. Although ceramics was only a very small part of what was on offer it did allow some students to experience clay for the first time and to consider that some form of artistic expression could be a part of their lives.

In addition to this, the ending of the period of wartime austerity had led to a proliferation of small ceramics manufacturing concerns. The Australian public were hungry for goods, and potteries across the country sated the desire of the consumer for colourful, relatively inexpensive items that faced little domestic competition in a highly protected market. The work may have been earthenware, and some may have despised the seemingly endless supply of eggcups and ramekins that flooded the market, but it was a business with a sound economic base.

At the same time, growing numbers of Australian potters, inspired by Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book, embraced the challenges of stoneware. The aesthetic was different and the technology presented many challenges, which doubtless was part of the appeal and explains the tendency of ceramics magazines to include copious amounts of technical information. There was a ready market for this new style of work, as it fitted well with the more avant-garde trends in architecture and homewares, although whether it ever had the same level of mass appeal as earthenware is debatable.

Growing numbers of commercial galleries exhibited ceramics and, because of the good prospects for sales, commissions were low and galleries wouldn’t dream of charging up-front costs. Exhibitions often sold out, and there are wonderful stories of gallery directors rationing sales to eager customers, such was the interest in this new field of studio pottery. However, the major development in the ceramics economy concerned the increasing amounts of public money flowing to the crafts. There were two main sources of this extraordinary largesse.

The first was the proliferation of government-funded ceramics training courses. In departments of further education, in vocational training and at art schools, the 1960s and ’70s saw an exponential rise in the adult education sector. Since ceramics was often a part of the school curriculum, teacher training colleges incorporated ceramics departments as well.

The result was that by the mid-70s even a small state might have a dozen or more fully functioning ceramics departments scattered throughout the metropolitan and regional areas. Many of these institutions offered a range of courses, with part-time and after hours ceramics classes being very well attended indeed.

All of these departments needed to be staffed and equipped, and a reasonably talented ceramicist might well look forward to gaining at least some of their income from teaching, with the most fortunate ones being offered the sinecure of a tenured position, together with generous working conditions and the prospect of a highly subsidised superannuation scheme on their retirement.

We also shouldn’t forget the students who, thanks to the Whitlam years, now had access not only to free education but a student allowance that provided (just) enough money to live on, which led to ever greater numbers of people moving through the art departments.

If this era saw an expansion of the higher education sector, it also witnessed another facet of government support for the crafts, which was the introduction of the grant, or should that be the GRANT.

As Grace Cochrane notes:

“Towards the end of the 1960s, the first moves were made to rationalise and co-ordinate the ways in which the federal government funded the arts, a development that was to reach its fullest form in the reshaped Australia Council for the Arts in 1973.”3

The newly elected Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, called on Jean Battersby, the CEO of the then Australia Council (originally an organisation mainly concerned with funding the performing arts), to prepare a report for the new government that highlighted the administrative and, from a strongly centralist government’s point of view, philosophical problems presented in overseeing the raft of existing arts funding bodies.4

Predictably enough, Battersby found that, “... the present situation is not satisfactory from an administrative point of view ...”5 To conjure the blessed spirit of Sir Humphrey Appleby, “steps needed to be taken”.

After all, Whitlam, with characteristic hyperbole, had stressed the importance of the arts to his new government, stating that,

“... all the other objectives of the Labor government – social reform, justice and equity in the provision of social services and educational opportunities – have as their goal the creation of a society in which the arts can flourish”.6

Never one to waste time, on Australia Day 26 January 1973, Whitlam announced the first appointments to a new arts council, comprising seven specialist boards, of which the Crafts Board was one. For the first time, the crafts had a seat at the adult table.

State governments followed suit, allocating funds through newly created departments of the arts to local crafts boards, which were often also funded by the Australia Council. Offices were rented, staff appointed and these organisations, state and federal, came to control the purse strings.

Not that the strings were drawn very tightly, at least in the beginning. Fiscal rectitude was not one of Gough’s strong points, and activities that had hitherto seemed to be the domain of the hobbyist – basket-weaving and the like – soon found themselves being encouraged and given financial support, and the mechanism by which this was achieved was the grant.

In an interesting historical coincidence, it was at about this time that the influence of a mainly American school of avant-garde ceramics, transmitted through the pages of that esteemed journal Craft Horizons, really began to be felt in this country.

This was a new type of ceramic work that was at the very forefront of post-modernism, revelling in its ‘dumbing down’ of high-art pretensions and poking fun at the rather serious and tasteful world of studio pottery. Unfortunately, these new ceramic objects were mostly unsaleable, and it is here that we begin to see the negative side of a system that supported artists to make things the public simply didn’t want.

This is such a complex equation that unravelling all the permutations should be the subject of at least one PhD. Suffice to say that the combination of providing government assistance for individuals to make work, together with rewarding many of those same individuals with teaching positions, as well as generously funding non-commercial gallery spaces to show work which was going to be very difficult to sell, led to a situation where many ceramicists didn’t take the attitudes of the general public into consideration at all, because they had no financial incentive to do so. This represented a paradigm shift in the relationship between Australian ceramicists and a public that had hitherto supported the crafts in a fairly enthusiastic manner.

There began an inevitable drift away from ceramics. Ceramics departments began to close down and the student numbers dwindled. The new management-driven class of education administrators (whose numbers were actually rising!) used this as an excuse to close more courses, and it just went on from there. Private galleries weren’t as willing to exhibit ceramics, because the sales had begun to drop off. They also charged a lot more for the privilege, regularly demanding up-front fees to cover costs, a punitive economic burden which the artist frequently tried to defray by – you guessed it – applying for a grant. Ironically, this practice was also adopted by government-funded spaces that found themselves in the privileged position of being paid (how shall I put this delicately?) to both give and receive at the same time.

Amidst all this discussion of the role of government in shaping Australian ceramics, what is to be said of the ultimate consumer, the so-called general public? What role have they played in all of this?

Tastes certainly do change, as does the availability of goods, and with it the way people choose to spend their money.

In the heyday of the crafts, inner-city shopping precincts barely had a coffee shop or restaurant to their name. Whole categories of modern consumer goods simply didn’t exist. This is significant because spending on the crafts is discretionary. The funds can just as easily be spent on something else, for example anything beginning with a lower-case ‘i’, or eating out.

Shops are now full of ridiculously cheap ceramics, mostly, but not exclusively imported from China, a country which has been pretty good at cornering a global market for export ceramics for over five hundred years. Whereas you simply couldn’t go into a store in the 1960s or ’70s and buy a nice set of plain white noodle bowls for a couple of dollars each, now you can get them at the supermarket. This is pretty serious competition for a potter who makes functional wares and it takes a very informed and dedicated consumer to spot the difference.

In the end, perhaps all one can really say is that in ceramics the distribution of government money

has had a definite impact on what is made, but then again so has the normal ebb and flow of the marketplace. The final arbiter of the arts economy is actually the secondary market, which is about as free as the free market gets, “... Nature, red in tooth and claw ...”7, though I don’t think Tennyson had Sotheby’s in mind when he came up with the phrase. It will probably take another fifty years to sort it all out.

Damon Moon

Willunga, 2012

- For example, Eros in Porcelain, an exhibition by the then Adelaide-based ceramicist Mark Thompson at the S.A. Craft Authority Gallery in May, 1976. A detailed review of this exhibition, written by Dick Richards, can be found in Pottery in Australia, Vol.15, No.2 p.66

- Timothy, chapter 6 verse 10

- Grace Cochrane, The Crafts Movement in Australia: a history, p.135 New South Wales University Press, 1992

- www.aph.gov.au/Library/pubs/BN/2008-9/ArtsPolicy.htm from a document prepared by Dr. John Gardiner-Garden 5 Jean Battersby, First Annual Report, January to December 1973 Australia Council for the Arts, 1973 p. 9

- Gough Whitlam, The Whitlam Government 1972–75, Viking 1985 p. 553

- Alfred Lord Tennyson, In Memorium A.H.H., 1850 (canto 55)

Gwyn Hanssen Pigott

“Instead, the things ... seep deliberately into one’s attention. They start vaguely, as little more than silhouettes, a vibration of one low colour against another. Gradually they ‘develop’ on the eye, and

one begins to grasp their internal relationships: how articulate the subtle sequence of tones may be,

in a form that once looked flat and brown; how many colours may be contained, as dusty hints and pearly afterimages of themselves, in what seemed to be a sequence of grey patches. If the straight side of a bottle seems to waver, it does so only to remind us how mutable and hard to fix the act of seeing really is. And if the shapes look simple, their simplicity is extremely deceptive; one recognises in it the distillation of an intensely pure sensibility, under whose gaze the size ... the silence of the motif and the inwardness of the vision are as one.”1

If not for the omission of six words in the passage above it might be assumed this article was one of the many recent tributes to the work of the late Australian potter Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, who passed away in London in July this year at the age of 78.

The missing words are ‘in his paintings’ and ‘of the painting’ and the 1981 essay by Robert Hughes is about the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, an artist who profoundly influenced Hanssen Pigott’s work and to whom history may apply a similar judgement of being a petit-maître, an artist who “... although (they) said it very well, had only one thing to say”.2

These assessments will be made and contested over time, but it is true to say that the reputation of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott as Australia’s most significant, internationally recognised ceramicist, is predicated on a body of work that took one idea and, balancing a sound knowledge of her craft with an acute sensibility, parlayed that work into a career that I doubt she could ever have foreseen.

In contrast to the rather hagiographic tributes being written about her life in ceramics, Gwyn’s progress did not always chart a smooth and steady rise. Nonetheless, her beginnings in ceramics are not so far removed from where they ended, especially when one takes into account the myriad digressions that have characterised the field over the last sixty years.

Several factors influenced her early career. As a student of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne she had ready access to the Kent Collection of Chinese ceramics at the National Gallery of Victoria, which at the time was the only readily accessible holding of historically significant Asian ceramics in the country. In an unusual but prescient move, Joseph Burke, then Head of Art History at the university, allowed her to research contemporary Australian pottery for her thesis. The Melbourne potter Harold Hughan introduced her to Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book, and so Leach’s persuasive arguments for the virtues of hand-made pottery, with its apotheosis in the ‘Sung standard’, could be immediately reinforced – ‘proved’ almost – by simply viewing the objects laid out before her in the gallery.

With Hanssen Pigott’s vision of ceramics having been realised (almost before it was formed) by the timeless beauty of classical Chinese wares, she quickly navigated the sea of rambunctious and gaudy earthenware that dominated Australian ceramics until “a very young nineteen-year-old in a dirndl skirt”3 arrived at the Sturt craft workshops in New South Wales where she met the potter Ivan McMeekin. There would be no turning back.

For Ivan McMeekin, who spent time in China before studying in England with Leach and Michael Cardew, the ‘Sung standard’ was accepted without question. When McMeekin returned to Australia from England to set up the ceramics workshop at Sturt, he sought to reproduce as closely as possible the classic wares of China, despite being separated from that originating culture by vast stretches of time and distance, and perhaps even of need. But McMeekin was tenacious and utterly convinced of his path and where he single-mindedly led, his young student followed. She took pressure off McMeekin by assuming responsibility for some of the teaching at Sturt, helpfully translating from the French the letters of the seventeenth-century Jesuit missionary Pere D’Entrocolles concerning Chinese porcelain manufacture, while digging for clay amongst the gum trees of the Southern Highlands in New South Wales.

When, with McMeekin’s blessing, she went to England in the late 1950s, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott set about furthering her education in ceramics at a time when Bernard Leach was the dominant figure and when his early apprentices were now leaders in their own right. Despite her commitment to this rather conservative approach to studio pottery, she also brushed up against a gentle version of modernism in London, where potters like Lucie Rie and Hans Coper had brought a ‘Continental’ sensibility to the field.

Gwyn Hanssen, as she was then, began to make a name for herself in London. Contemporary commentators remarked on her work as being “... completely acceptable ... a potter’s potter ...” 4 whose work “... more or less summarises the Leach-Cardew-Davis-Finch field ... akin to the work of the Mackenzie’s in the USA and McMeekin in Australia”.5 Pottery that belonged to the tradition of “Workshop potters versus art school potters. Useful-ware potters versus sculptor-painter-potters”6, this last observation having particular resonance when viewed in the light of her later work.

A typical example of her output at the time, from a 1962 exhibition at Primavera gallery in London, was almost a craft cliché: a ‘punch set’ consisting of cups with handles, a large, footed bowl and a ceramic ladle, all in muted, ash-glazed stoneware. And although Alison Britten, writing of this period in her essay ‘Gwyn Hanssen Pigott: a view from her second home’7, recalls that she represented a “... benchmark of sound and sensitive practice ...”8, other commentators had a different view, with Robert Melville, writing a few years earlier in Architectural Review, remarking that much of the ceramics coming out of the crafts movement seemed to belong to a “... village and market town community of highly aesthetic peasants ...”9

Gwyn Hanssen Pigott would soon reinforce this commitment to tradition (and here the word ‘tradition’ needs to be understood as being as much notional as factual) and by the mid-sixties, inspired by the simple beauty of French domestic pottery, she had settled in the district of Haut-Berry a few hours south of Paris. She built a large woodfired kiln and used local materials in a direct extension of McMeekin’s purist methodologies, which he in turn had inherited from Leach. (In truth, Leach was quite willing to modify his purist approach for the sake of expediency – it was more the early students like Michael Cardew and Harry Davis who took some of his philosophical urgings to what can only be described as fanatical extremes.)

She made pots in France and travelled often to England, where she supplemented her income by teaching at various art schools. Gwyn Hanssen Pigott had become a highly regarded maker of functional pottery, as good as any in the business. She was also very aware of the contradictions and paradoxes that ran through this modern, largely middle-class obsession with traditions that had faded away, when as early as 1969 she wrote that “... we younger potters ... can never be ‘potters of Haut-Berry’ ... we can never recapture the spirit that has passed. We remain, as ever, our immigrant selves, alone always, our work our own personal struggle and delight”.10

Later she recalled that she had “... tried ... to make something which would be real. I hoped that if I lived like a traditional potter somehow I would make pots like those unpretentious craftsmen in times gone by. But in fact I wasn’t unpretentious at all – nor simple ... I was acting a part that I hadn’t the strength for, and I was caught in a very subtle ambition to which I saw no end”.11

What is apparent from this statement is that Hanssen Pigott already had the ability to see beyond the objects she was making in order to interrogate their place in the world and, by extension, to question her own role as a contemporary craftsperson. This ability (which is rarer than one might think) does not necessarily lead to comfortable conclusions, and it probably contributed to her decision to leave her “... French idyll taking only what I could carry in my bag”.12

In 1973 Gwyn Hanssen Pigott returned to Australia. She worked for a while in New South Wales, and in 1974 moved to Tasmania where, with her student and future husband John Pigott, she established

a pottery near Hobart. During this time she returned to the methodologies that had characterised her work in France, making functional ceramics from locally sourced materials. The curator of Hanssen Pigott’s 2006 retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Jason Smith, states that this time shows her “starting again”13, but she was also repeating herself, just in another place.

Her move in 1980 to the JamFactory workshops in South Australia resulted in a more substantial shift in her working practice, in that she found a way by which the effects she sought could be achieved more efficiently, albeit without any significant alteration to the final product. As ever, change in Hanssen Pigott’s work came incrementally. Change in location happened more frequently.

In 1981 she moved to Brisbane, becoming a resident potter at the Kelvin Grove campus of what is now the Queensland University of Technology. Over the next eight years, Hanssen Pigott continued to make functional pottery, even pursuing the decorated surface before “... reinvesting in simplicity ...”14

If functional, production-based pottery had maintained a certain cachet during the sixties and seventies, by the 1980s its allure was wearing a bit thin. The challenges first mounted on the Leach- derived studio pottery tradition by modernism and the Funk movement had evolved into a myriad of divergent styles; all clamouring for attention, all given equal time within the ceramics community, all suffering from the same lack of critical analysis that typified the discourses surrounding the Crafts and – with one or two possible exceptions - all being ignored by those working in the fine arts.

Working in the environment of an art school, the widening rift between ceramics made as art and studio-pottery was apparent. As Jeff Shaw, then Head of Kelvin Grove CAE, wrote of a 1983 exhibition of Hanssen Pigott’s work at Blackfriars Gallery in Sydney: “Gwyn’s ware is simply practical and simply beautiful, unpretentious but carefully considered. It is a pleasure to use and view.”15 Which is all very nice, but it doesn’t make it art and it meant that, as Jason Smith notes, Hanssen Pigott was increasingly being written out of the critical discourse.16

And then something happened.

The precise moment that Gwyn Hanssen Pigott began to group her pots together as a statement may never be known. The transition from casually observing thousands of pots sitting side by side on ware- boards or in the kiln, a familiar

sight to anyone who, like Hanssen Pigott, was a production potter, to the conscious grouping together of objects so that the whole was more than the sum of the parts probably happened slowly. Those who knew her from earlier times comment that she often would take great care in selecting and placing objects in her own home, with the same degree of care and control that typified her approach to all aspects of her craft.

A grouping titled Three Inseparable Bowls was exhibited at the Gary Anderson Gallery in Sydney in November 1987 and her adoption by this dealer gallery, more known for representing fine artists than craftspeople, certainly played its part in situating her work within a wider context. (Interestingly, the Gary Anderson Gallery staged a group exhibition in 1990 titled Homage to Morandi which featured many well-known artists, including Alan Mittleman, John Peart, Leonard Brown and Kevin Lincoln.)

A picture of Hanssen Pigott’s 1987 work, together with a short artist’s statement, can be found in the February 1988 edition of Pottery in Australia and it marks a bellwether moment in Australian ceramic history. Hanssen Pigott states that the “... bowls, bottles, beakers or teapots (are) ... meant as much for contemplation as for use; but whether studying them will yield any sense of meaning is questionable. They are only about themselves and about the years of needing to make them ... I can’t offer them as new, surprising, noble or comfortable. I have to make them because they are beautiful, worth the trouble”.17

There may be some argument as to whether these three bowls, taken individually, were new (metaphorically if not literally). The term ‘surprising’ doesn’t spring to mind; they were comfortable in the sense that were in no way challenging, and as to the question of nobility – well, “What poor an instrument, may do a noble deed”18 probably sums it up, if one takes poor to mean humble, or even self-effacing.

But that is if the pieces are seen individually, which of course they can’t be because they were ‘inseparable’, and therefore were one. Viewed through the finely tuned lens of Hanssen Pigott’s later work, these three bowls are very much a beginning. They only hint at what might come, but their significance to the artist is demonstrated by her reference to a poem which reads:

Some men go ten years without crying and when they do cry