Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

Currently in its fifth generation of family ownership, Bennetts Magill Pottery in Adelaide provides one of the last remaining glimpses into the small- to medium-size manufactory that was the mainstay of Australian ceramics throughout the nineteenth and into the first part of the twentieth century.

The founder, Charles (Chas) Bennett, was born in Somersetshire in England in 1842. In 1849 he travelled with his family to the newly established colony of South Australia, settling in Magill, then a semi-rural area a few miles east of the centre of Adelaide. Good supplies of clay, as well as abundant fuel in the shape of the string-bark forests cladding the adjacent hills, ensured the area quickly became home to a number of potteries, established to fulfil the needs of a rapidly growing population.

Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

The young Charles Bennett gained an apprenticeship at just such a pottery, run by a Cornish immigrant, third-generation potter named John Henry Trewenack. From the age of twelve, Bennett worked at Trewenack’s, first as an apprentice then as a full employee, where he spent many years learning about all aspects of the craft. In 1883, Charles Bennett, together with his son, William Charles Bennett, worked for a time at the nearby Piercy brothers pottery and it was there that the young William Bennett met his future wife, Abigail Piercy, forming a union that perhaps ensured the future importance of ceramics to the Bennett’s clan. Clay, it seems, was in their blood.

photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

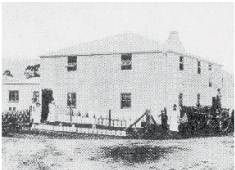

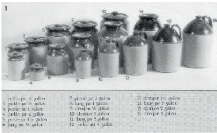

Following the death of William Piercy in 1885, the business went into decline, prompting the Bennetts to finally establish their own pottery on land the family owned at Magill. The pottery started trading at a date towards the end of the 1880s (the actual date is given variously between 1887 and 1890). Initially consisting of a shed, a horse-drawn pugmill and a small wood-fired kiln, the Magill Pottery Works, as it was called then, was gradually expanded to include a bottle-kiln, larger workshops and some mechanisation in the shape of steam or oil driven engines, thus relieving the horse of its more burdensome duties. Further equipment was added with the purchase of new throwing wheels manufactured by the English company of William Boulton Ltd, by which stage the pottery, now called C. Bennett and Sons, was producing a vast range of the kind of useful, no-nonsense pottery needed by homes, farms and industry – bread crocks and mixing bowls, preserving jars, acid, wine and spirit jars, butter coolers, poultry waterers, and garden and chimney pots.

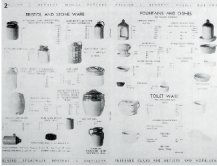

During the 1920s and 1930s, the pottery, now under the management of William Bennett, continued to increase the range of goods on offer. In addition to an assortment of terracotta pots there were several types of glazed domestic wares, although, in keeping with the mainstream of Australian ceramic practice, no fine dinnerware was produced, this market being met by imported English ceramics. Further to this, a range of highly successful ‘art pottery’ was produced, with vases and other decorative items being glazed in a variety of mottled and streaked lead-based colours, often referred to as Majolica or agate wares.

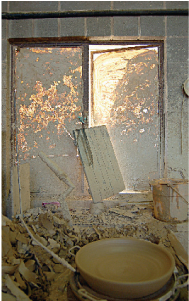

photo: Damon Moon

There were, however, setbacks. On the morning of 27 November 1940, a fire razed the building to the ground, leaving a total damage bill of around ten thousand pounds. The pottery was rebuilt, but by the time an official of the Department of Mines visited the factory in 1946, the pottery had returned to its core production, where:

Bennett’s products are largely confined to a stoneware and coarse domestic ware. Acid jars are thrown on the wheel … Bristol ware is … [made] … from Tea Tree Gully clay with some Woocalla ball clay added to extend the vitrification range.1

By 1950 the pottery was being run on a day to day basis by the third-generation William Reginald Bennett. The kilns were now fuelled by oil, which, unfortunately, did not prevent a second massive fire from destroying the pottery in 1956. Reginald Bennett seriously considered whether to rebuild the pottery, but since his own son, Robert William Bennett, was now working at there, it was decided that the business would continue.

In 1964, Robert assumed control, in a marketplace where conditions were changing rapidly. Although the majority of garden wares used in Australia were still produced locally, the lifting of post-war restrictions had allowed an ever greater amount of imported ceramics to enter the market, a move which led to the demise of many of the small manufactories which had sprung up in the immediate post-war years. Bennett’s responded to this decline by diversifying their manufacturing base, for a time even supplying bricks to a booming building industry, but also, conversely, by sticking to their guns and continuing to make a range of utilitarian pots almost identical to those they made in the late nineteenth century. A growth of interest in the crafts throughout the 1970s saw these traditional pots come back into fashion, while the proliferation of ceramics courses and increasing numbers of practitioners provided a ready market for Bennett’s clay. With the closure of Koster’s Pottery in 1977, Bennett’s was left as the sole South Australian pottery operating along more or less traditional lines.

In the mid-1970s, Robert’s son, John William Bennett, became the fifth generation to work at the pottery, and he now runs the business in a family lineage that spans three centuries. The last twenty or so years have seen added pressure on the business from imported garden wares, but Bennetts endures, providing a fascinating link to the vernacular ceramic traditions of the past.

Photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010