A Potter's Tale

Everybody has a story to tell and potters are no exception. Before the days of tweets and blogs, telling that story to a wider audience meant going into print. In most cases this meant writing an article for a ceramics magazine, but some potters managed to go one better than this and have a book published. These books mostly concentrated on aspects of materials or technique, but occasionally a potter would write about ceramics in a wider context and in the process they would tell a story.

This essay is about a few of these books. Most of them are relatively unknown, little gems in what must be considered one of the more obscure branches of publishing. I haven’t chosen them for their inherent literary merit or even for the wealth of information they convey. More than anything else I like the sense of honesty these books have – they are very true to themselves, which is not a bad thing.

So, without further ado, and in no particular order, here is my selection.

The Story of Palissy the Potter

T. Nelson & Sons, Paternoster Row, Edinburgh and New York 1876

This is one of the oldest books I own. Originally given as a ‘Prize for Reading’ to an Alice Lade in 1877, it was bought by my father in the early sixties, and his name is inscribed on the first facing page under the original dedication. It is a beautiful little book and includes two colour-plates. The first is titled Palissy’s Final Experiment and shows the potter sitting at a table mixing ingredients while his wife stands behind him holding their baby, while all around them on the floor are smashed pots. Reading the book it is apparent that it shows Palissy using fragments of pots to conduct glaze-tests, which just goes to show that some things never change.

The second picture shows Palissy placing a pot in a kiln, which really looks more like a fancy bread oven with its neat cast iron door and polite little fire burning in the hearth underneath. This is Palissy hard at work trying to fire the aforementioned glaze-tests so he can discover the secret of what is referred to as ‘a white enamel’, which we would call a white glaze. This part of the story is perhaps the only thing that is now remembered about the whole tale, where Palissy is forced to burn the palings from his fences and then even the household furniture, all the time trying to gain sufficient heat to melt the glazes.

The story is set against the fierce religious persecutions of the Protestant Huguenots by Catholics in 16th century France, and, unfortunately, Palissy’s life ends badly, locked in the Bastille by evil Papists.

It is meant to be a tale of triumph over adversity, but – at least from a contemporary standpoint – the messages are very mixed. Starving one’s kiddies and burning the furniture in order to get a good glaze?

This book might appear to be an eccentric period-piece, but one of the curious facets of the text is the way it has parallels in some far more contemporary tales concerning the triumph of the will in a world of ceramic adversity.

Potbank by Mervyn Jones

Secker & Warburg, London 1961

Potbank: A social enquiry into Life in the Potteries was the first in a series of texts published as part of the ‘Britain Alive’ series in 1961. It’s author, Mervyn Jones, was not a potter, but the picture he paints of life in the once-great ceramic centre of Stoke-on-Trent rings very true.

The six towns that make up the city of Stoke-on-Trent (Longton, Hanley, Fenton, Burslem, Tunstall and Stoke) known collectively as ‘the Potteries’, are represented here in all their sooty splendour. In fact, if this book were a film it would be in black and white, with factory girls riding home from work on old Raleigh bicycles down cobbled streets lined with identical terrace houses. The language is chock full of colloquialisms, hence the term ‘potbank’ for a factory that makes pottery, or ‘paste’ for the clay slip for casting porcelain.

It is a world as far away as can be imagined from contemporary ceramics with its art schools, grants and galleries, while still working with the same basic materials, except that they did it so much better, or at least much more skilfully.

And the writing is charming and very English – here is an example:

Tower Square, in Tunstall, is to my mind the prettiest ... This is a peaceful, open square, with a sniff of fresh air and a lingering memory of a country market town. It is ridged in the middle, so that the houses seem to lean outwards. Mostly they are small, unassertive shops, selling things like jigsaw puzzles, goldfish food, and the libraries of defunct clergymen.

For all the faddishness of Jin de Zen, we shouldn’t forget that the vast bulk of Australian ceramic history lies in England, or that the wealth, skill, scale and success of the manufactories of Stoke-on-Trent are a singular moment in manufacturing history.

This book certainly doesn’t paint a romantic picture of life in the factories, and I doubt if many of the Mashiko-bound potters in 1961 would have altered their destinations to the English Midlands after reading it. Nonetheless, it gives one a taste of an industry that, in its heyday, supported thousands of workers and, together with the mills, steel and shipbuilding, made Britain great. Now, just let me check if that souvenir cup from Kate and Wills’ wedding was ‘Made in China’ ...

May by May Davis

Self published May Davis, New Zealand 1990 ISBN 0-473-01000-3

After reading this autobiography by May Davis, one wonders that she had the energy to write anything down at all, given the almost ridiculous extremes of discomfort she endured at various times and places to, together with her husband Harry Davis, make pots that people might sometimes have wanted but, in reality, nobody actually needed.

Bright, artistic and beautiful, born into a privileged household (her grandfather was the founder of the Manchester Guardian, later to become The Guardian newspaper), one is left with the overriding impression that May Davis might have had a far easier life if she had just ... well, if she had just not met Harry Davis.

Then again, one wouldn’t want to convey the impression that May Davis was a shrinking violet, blindly following ‘her man’ as he travelled around the world on yet more arduous ceramic adventures. Indeed, as is obvious from the text, May was a little bit ‘out there’ herself, wholeheartedly identifying with various causes, sometimes to the detriment of both her personal life and health. This, combined with her husband’s proclivity for taking on large challenges of a ceramic kind, make Harry and May Davis an interesting case-study in both how to conquer difficulties and yet at the same time make

the easy difficult and to render success, if not a failure, then at least hard to savour by virtue of sheer bloody-mindedness.

Of all the biographies included in this essay, May is probably the most ‘tell all’, in that it eschews almost all detail about the making of pots while including a great deal of detail about the life of the author. To be honest, there is a bit ‘too much information’ for me; the details of May’s first orgasm, clutching Harry’s knee as she sat beside him, fully-clothed and still decidedly in possession of her virginity, is interesting as far as it goes, but there is also surely something a little vain about recounting such an episode; as one reads further, it becomes apparent that the text is characterised by such observations.

Don’t get me wrong. This is a very gutsy woman we are talking about and she did not let herself

be constrained by either societal expectations, or indeed by any regards for her own comfort. One also realises that it was all too easy for the male partner, in what was undoubtedly an equal working partnership, to become widely recognised while the woman was considered a kind of willing helper. In fact, reading this text it is clear that May Davis was deeply involved in all aspects of both making and selling the work. What she didn’t do was embark on the numerous lecture and workshop tours that Harry Davis undertook, tours which served to raise his profile in the international ceramic arena while May Davis attended to business and family at home.

Both the Davis’s were up for a challenge, but going to live in extremely adverse conditions in Peru

in the early nineteen-seventies seems to have been one adventure too many, at least for Harry Davis, who returned from this adventure with his health seriously compromised. This was the last in a series of South American adventures that must have sorely tested their endurance even when young and fit, let alone when they were approaching late middle-age.

As May Davis herself asks, the question remains as to whether this kind of interventionist project (one could add Ivan McMeekin in the Northern Territory, Michael Cardew in Africa) actually achieves very much, or merely perpetuates a kind of benign cultural condescension. At least in the case of Western potters visiting Japan the shoe was, for once, on the other foot, but that is a discussion for another day.

And, having mentioned Michael Cardew, perhaps it is appropriate that the next text to be discussed is by the original pioneer potter himself.

A Pioneer Potter – An Autobiography Oxford University Press, 1989

ISBN 0-19-282641-7

The greatest disappointment to be had from reading Michael Cardew’s A Pioneer Potter – An Autobiography comes when one realises that it is indeed only half an autobiography, as it ends in 1948 with Cardew returning to England from the pottery he established at Vumë in West Africa. According to the book’s postscript, written by his son Seth Cardew, notes written by Michael Cardew before he died in 1983 indicated his intention to write about his later career: the return to Africa, then back to England in 1965 at the age of sixty-four, and lastly his prominence as an international ceramics celebrity, touring and giving workshops throughout the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Alas, it was not to be, so we only have this attenuated account of his own life, by his own hand.

Cardew’s most famous book, of course, is his 1960 Pioneer Pottery, a compendium of materials and techniques for making pottery – or, more precisely, stoneware pottery – in places where neither

the tradition nor maybe even the need for such wares existed. As such, his entire production in Africa involved the augmenting of an effective indigenous tradition of low-fired wares with a curious amalgam of Anglo Oriental stoneware that itself was influenced by English slipwares and local African patterns, if not forms. It was a curious enterprise, and one which kept Cardew occupied for much of his life.

However, the pottery that Cardew made at the beginning of his career came from a tradition much closer to home. As a young man he had fallen in love with English slipwares, and this fascination even intruded into his study while a Classics student at Oxford. And in a curious way this says it all – on one hand we have a well-educated young man, studying ‘the Greats’ at a prestigious university and playing classical music in his spare time. On the other, we have a driven individual who has fallen in love with a remnant, almost extinct, tradition of rural ceramics and who is intent on reviving that tradition, despite the fact that it has been utterly supplanted

by industrial wares and can in fact probably only really survive as a token or facsimile within the fragile and precious world of the gallery and collector.

In fact, Cardew’s chapter in A Pioneer Potter titled ‘Who Makes These Wonderful Things?’ describes in some detail the moment when he found that he could, as a relatively young man, enter into the world already inhabited by Leach and Staite-Murray, when his pots, included in a group showing of the newly formed

National Society of Painters, Sculptors,Engravers and Potters, met with great financial and critical success. Of course Cardew ran a mile, and the wonderful thing about this book is that he is so transparent in recounting the details of these and other moments of success and failure, indecision and passion in a voice which is neither too distant, or too self-involved.

Other aspects of his life and career, including his prolonged absences from wife and family, are explained in a way which throws further light on his attraction to Africa. The personal conflicts thus hinted at might also account for his famously difficult nature, but instead of May Davis’ rather confronting admissions, Cardew just gives us enough information to figure it out for ourselves.

A Pioneer Potter is not a charming read, but it is clear-headed, erudite and one just wishes the old devil had lived long enough to finish it.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2011

Another Still Life

In 1997, together with Suzi Attiwill, I curated an exhibition held at West Space Gallery in Melbourne.

The purpose of the exhibition, Curated, was to examine what curators did, as what curators were doing seemed to be gaining ever greater prominence in the art world, at times even eclipsing the role of the artist.

This was especially noticeable in the contemporary arts but was also being seen in exhibitions of historical works by ‘star’ international curators, as well as the increasing numbers of artists who used curatorial processes and curatorial places as the raw material for their work. (The American writer Lisa Corrin describes museum-critical art as being so ubiquitous that it was deserving of its own ‘ism’, as in ‘museum-ism’.

It sounded a simple enough idea, but the trick lay in how it was to be done.

This is what was decided upon, as it appeared in the catalogue to the exhibition.

Curated

6 curators; 6 different curatorial responses.

Location: West Space Galley Inc.

Curators: Suzi Attiwill and Damon Moon plus six curators.

Time: 16 October – 1 November 1997.

Outline: Six curators have been allocated a space in the gallery within which to explore any aspects of curatorial practice they choose and in whatever way they wish. There is one stipulation only – as the object is not to have six mini shows of artists’ work but to exhibit curatorial practice, no original artworks are allowed.

The invited curators include those who have worked in different gallery spaces, such as public institutions, university galleries and artist-run spaces.

The two main galleries are occupied by the six curators. The smaller space displays documentation associated with, and produced in the making of, the exhibition. The office continues in its role as a mediated space between the gallery infrastructure and the exhibition.

The boundaries of the exhibition extend to include a forum, Jack High, to be held at West Space and a dedicated issue of the journal Dialogue called Greens.

Currently there is increasing debate about the role of the curator in contemporary visual arts practice. Curated attempts to make this role visible in different ways.

As curators we are seeking to make visible the curatorial practice within the gallery space. We, as curators, will curate curators curating themselves.

Suzi Attiwill and Damon Moon.

(I’m not sure now how the lawn bowls metaphor worked its way so thoroughly into the project, but it seemed appropriate at the time.)

We invited a number of curators to participate in the project, and – perhaps surprisingly – almost all accepted. We also invited one artist, Sandra Bridie, whose practice included a curatorial alter ego, B.S. Hope.

Aside from Sandra Bridie, the curators were Natalie King, Stuart Koop, Jason Smith, Peter Timms and Rachel Young. Maudie Palmer included the exhibition as part of the visual arts component of the Melbourne International Festival and Julian Burnside QC generously agreed to fund the project. In addition, a number of writers, curators and academics took part in a forum broadcast by the ABC and contributed articles to an issue of the journal Dialogue published to accompany the exhibition.

All in all, the whole thing was extremely well organised and well executed but, given the limitations placed on the curators, what did a visitor to the gallery actually see?

In the first room Natalie King used wall text to reproduce quotes from various authors and artists. Rachel Young altered a wall by painting it a deep burgundy colour and Stuart Koop installed shelving, modelled on the type one finds in a greengrocers, which he then filled with oranges, ensuring that this room not only looked beautiful but smelled good as well.

In a second room Jason Smith covered a desk with correspondence received in his position as Curator of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Victoria. This included the infamous ‘Rothko letter’, a …’form-letter … developed in response to regular enquiries received concerning the correct display of a Rothko painting owned by the NGV’. (Apparently people were always writing in concerned it had been hung upside down.) There was also a tape recording of messages left on his answering machine, a strategy which probably caused some trepidation amongst sectors of the Melbourne arts community but was nonetheless quite funny and added a certain chattiness to the proceedings. On the wall was a line of photographs of Sandra Bridie posing as the aforementioned fictitious curator B.S. Hope going about her business as a fictitious curator, and on the floor was Peter Timms’ curious small sculpture of a distorted jigsaw puzzle incorporating a picture frame.

In other words, most of the curators chose to work with mechanisms of display or documentation. Only Peter Timms opted to make an object that was …’a … metaphor of the curatorial process’ without directly referencing those processes.

The exhibition certainly looked good, in a cool and considered way. Thanks to Suzi Attiwill it was beautifully designed and it had a strong curatorial premise which led to ‘valuable outcomes’ in terms of publications and debate, and it seemingly didn’t suffer at all from the fact that it was an exhibition without art. (Unless of course you count Sandra Bridie’s contribution, which made an art out of pretending not to be art.)

Now, at this point the perceptive reader will offer the rejoinder that as soon as these objects were displayed within an art gallery they simply became art. To which I could counter that since these things were deliberately nominated as being not art it would be ascribing a great deal of power to the gallery to imagine it could turn everyday objects into art, like water into wine.

Yet, to all intents and purposes, this is exactly what happened, and what’s more I bet no one reading this article who has any knowledge of the contemporary arts would find this in the least bit surprising.

Curated went beyond the now accepted boundaries where artists place just about anything into the gallery space in the name of art by demonstrating that you actually don’t need the artist at all. All you need is the designated place of art and people who are practised in using that space, something which obviously has important ramifications for the training of artists.

Before investigating what these might be, I’ll cite another example of this phenomenon whereby everyday objects are transfigured in the name of art, this time involving the work the Australian potter Gywn Hanssen Pigott.

Hanssen Pigott has become very well known for making pots which she then arranges in groups, on the understanding that these groups of pots constitute the artwork. (The power of Hanssen Pigott’s oeuvre has been so widely felt, especially in the crafts, that another ‘ism’ is probably called for, perhaps as in ‘arrangement-ism’.)

Lately she has taken this idea further, by arranging ceramics she has not made. This can be seen in her exhibition ‘Parades – Freer Ceramics Installed by Gwyn Hanssen Pigott’ at the Smithsonian Institute, which involved choosing ceramics from the collection which were then exhibited in that institution.

These arrangements, or installations, were each given titles – ‘Still Life with Pickle Jar’, ‘Garden’, ‘Remembrance’, ‘Blue Parade’, ‘Trail with Pale Bowls’, ‘Float’ and ‘Studio’ – with the objects chosen by the simple expedient of deciding if they looked good together. According to the Smithsonian’s press release, she …’ignore[s] place and date and focuses wholly on colour, form, pattern and relationship, [demonstrating] a curiously sympathetic approach to the taste of Charles Lang Freer who acquired most of the selected objects a century earlier.’

This begs the question as to how one could possibly fail in that attempt, given the extraordinarily beautiful nature of the objects involved and their underlying similarities. What is certain - and here one might applaud Hanssen Pigott for her bravery in the ‘Yes Minister’ sense of the word - is that in these arrangements each of the component pieces are literally of museum quality, whereas in the case of her own works the individual pieces are often quite nondescript.

In the case of Hanssen Pigott’s work at the Smithsonian, her actions were deliberately designated as being not curation. This was reiterated at a talk I attended at the Art Gallery of South Australia where she described the suggestion of a curator at the Smithsonian regarding the addition of a small white bowl to one of the arrangements as being made on aesthetic grounds – how it looked - in contrast to the more usual criteria associated with arranging works in a museum around an idea – what it meant – something which has long served to differentiate the roles of artists from curators.

The fact that Hanssen Pigott didn’t make the individual pots doesn’t lessen the arrangement’s putative or actual status as art. In fact, there was a kind of ‘value adding’ at work here, whereby the collection is imaginatively re-configured to the benefit of both the institution and the artist, and, hopefully, the audience. In addition, there are magnificent photographs which remain as documents and have at least the possibility of existing as artworks in their own right. (I will leave vexed issues of photographer and copyright to the reader’s imagination.) A further benefit was that the whole project had a very much longer life than the usual commercial gallery exhibiting cycle, being on view for over a year.

By virtue of her status as an artist Gwyn Hanssen Pigott was accorded the rare opportunity of using an existing collection to make a new work, but I suspect that any practised curator could have achieved the same result, albeit without the marketing advantage a ‘name’ undoubtedly brings.

In these case studies it seems we are being presented with radical models of how meaning is constructed in two quite different areas of the visual arts, but they are just overt examples of a process which occurs all the time, whereby the mechanisms of display and consumption that surround a work are often as important as the work itself, sometimes more so. The implications for the training of the artist, or more accurately for those institutions that assume the role of training, are profound.

For a start, any idea of the de facto primacy of the individual, newly created artwork must be questioned, yet in my experience the student is inculcated with the notion that the act of creativity is all important. They are led to believe that their artistic lives depend on accomplishing an almost impossible task, that of coming up with something original in a society which is drowning in images and objects. It’s unfair and it’s counterproductive. The more emphasis placed on what is yet to be made, the less chance anyone will have the time or inclination to learn anything from what already has been made.

A truly radical model for art education would recognise that things should be made, but not new things; techniques should not be taught as a means to an end, but practised as an end in themselves; and a great deal of attention would be given to appraising how art reacts with the space around it, be that a physical or cultural space, and how the physical or cultural space in turn dictates what becomes art.

If at the end of all this the desire is there to make something new then it will stand a much better chance of really being new. But then again, everything old can be new again.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2011

Vale - Shiga Shigeo 1928-2011

With the passing of Shiga Shigeo, Australian ceramics has lost a great and long-standing friend.

There will be many tributes from those who knew him intimately, and these few words are simply to acknowledge the presence, and now the absence, of a Zen larrikin who found, at least for a time, a second home in Australia.

In any analysis of Australian ceramics the abiding influence of Japan is of great significance and in this singular and fascinating relationship between the two cultures the figure of Shiga is prominent. For all the hundreds of Australian potters who took the ‘Mashiko express’ in the 1960s and 70s, Shiga was one of the few took the journey in the other direction. First in Mittagong, then in Sydney, he inspired and delighted Australian potters for the thirteen years he spent in this country. Even after his return to Japan in 1980, Shiga maintained close contact with Australia and with the many Australian potters who revelled in his company.

There are many Japanese potters that have won the admiration of Australian potters, but few who came as close in spirit to this country as Shiga. From Tokyo to Terrey Hills and back again is a fair way, but it was the journey that Shiga made, and we are grateful that he did.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2011

Editor’s note: In our Archive section, pages 98-100, I have reprinted Shiga’s farewell speech (from Pottery in Australia, Vol 18, No 2, October November 1979) given at the opening of his retrospective exhibition at the Japan Foundation Centre in August 1978 just before he returned to Japan after thirteen years in Australia.

Vale - Paul Soldner 1921 – 2011

In early January 2011, Paul Soldner, one of the greats of American ceramics, passed away at his home in Claremont, California. He was eighty- nine.

Born in 1921 into a family of Midwest Mennonite Christians, Soldner’s interest in art was sparked by his wartime experiences in the army medical corps, where, to quote Jori Finkel writing of Soldner in the Los Angeles Times, he saw ... “beauty emerge from terror in the form of charcoal drawings made by Holocaust victims on the barracks walls of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria”.

(Frinkel, J. Los Angeles Times 4 January, 2011)

In 1954 Soldner became the first graduate student of Peter Voulkos in the newly established ceramics program at the Los Angeles County Art Institute. Like Voulkos, Soldner was given to experimentation and innovation and was also something of a showman, soon becoming what Garth Clark refers to ... “as one of the stars of the “workshop circuit”. (Clark, G. Shards, p.289)

It was during one of these workshops that Soldner famously ‘discovered’ his technique of ‘American raku’, where pots were drawn from the kiln and then ‘smoked’ in various ways to produce a range of effects much broader than those found in the original Japanese technique. But Soldner’s oeuvre extended well beyond this, encompassing a wide range of ceramic techniques and forms.

Paul Soldner was a charismatic teacher and tireless maker who came to prominence at a time and in a place when ceramics was breaking many boundaries. He continued to contribute to the development of ceramics both in the United States and on an international level throughout a long and productive life, and he will be both celebrated and missed.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2011

Perspective

“I cross the room like a dancing architect

A daddy waltz on the tops of my shoes ...”

Let’s face it – architects are cool. They wear good clothes, have distinctive taste in spectacles and build fabulous, titanium clad post-modernist cathedrals to art which rejuvenate entire cities. Even in the fraught and over-hyped world of contemporary art it’s obvious that the star attraction of the Bilbao Guggenheim is the building and its architect, Frank Gehry, and not the art inside.

On the other hand, ceramists are not really cool and probably never have been. There may have been a certain cachet afforded to the hand-spun, tie-dyed and hirsute in the 1960s, but ceramics has really always been just this side of macramé as far as the mainstream arts establishment goes, and it probably always will be.

Given this, it might seem strange that in the early days of the post-war Australian crafts movement architects featured prominently in generating support for the crafts. They encouraged craftspeople to extend their vision by commissioning works for buildings, by helping with exhibition design, by collecting works to be shown in their own and in client’s houses, and by participating in an active dialogue as to how the built environment and the hand-made object might co-exist in the modern world.

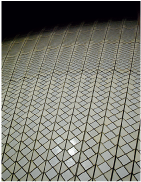

Sydneysiders should be more aware of this than most, since they have in their midst one of the greatest examples of twentieth century architecture in the shape of the Danish architect Jorn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, a building totally covered with white ceramic tiles. One might fairly ask if the tiles, made by the Danish firm Höganäs, are the product of craft or industry, or indeed are any more significant than the ubiquitous clay bricks from which the majority of Australian houses are constructed. But what this building represents, at least in part, is the emphatic arrival of a Scandinavian design aesthetic in Australia, and with it the promise of an integration of crafts and industry, an ideal which now probably falls into the category of ‘nice work if you can get it’ but which, nonetheless, had much currency at the time.

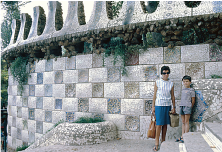

If only a few modern buildings were entirely covered with ceramic tiles – and, after all, the Muslim world had taken this technique to heights of extreme beauty and sophistication hundreds of years before – then the fifties and the sixties also saw a rebirth of interest in other ways to marry ceramics to architecture. One was in the use of mosaics, with perhaps the greatest example being Antonio Gaudi’s Guell Park in Barcelona, where the order and discipline or the traditional tiled ceramic surface is literally shattered into a colourful, fragmented universe of inspired crazy-paving.

A related use of architectural ceramics was found in feature walls or panels, which had the advantage of being able to be either outside or inside a building, due to the ability of ceramics to cope with harsh environments. The artistic partnership of the painter Joan Miro and ceramicist Jose Llorens Artigas gave us monumental outdoor panels in the 1957/59 Wall of the Sun and the Wall of the Moon for the Unesco Building in Paris, work so important that it led to Miro receiving a Guggenheim award in 1958. (Ironically, these artworks are now enclosed by a building in order to protect them from the effects of acid rain. Perhaps ceramics are not quite as durable as we think ...) Some Australian examples of public ceramics murals, as in Vincent McGrath’s three metre by eleven metre Wall, completed in 1980 for the Attorney General’s Department in Alice Springs, are mentioned in an excellent article by Romaldo

Giurgola, one of the architects of the new Australian Parliament House. This article, first published in 1984 and now reprinted in this issue of The Journal of Australian Ceramics, gives an insight into how one of this country’s leading architects sought to incorporate the work of Australian craftspeople into the very fabric of this important building (if that isn’t mixing metaphors) right from the planning stages.1

On a more intimate scale, the interiors of 1960s architect-designed modernist houses, with an emphasis on natural surfaces largely free from overt ornamentation, provide a wonderful setting for ceramics of the period. There is a certain ‘rightness’ in seeing stoneware ceramics displayed in this setting, whether as tiles, functional pottery or decorator pieces.

For example, in the ceramics of Marea Gazzard one sees a sophisticated take on the vessel as domestic sculpture. Before studying in Europe in the 1950s, Marea Gazzard, who was married to the architect Don Gazzard, had been exposed to the work of avant-garde British ceramic artists like Lucie Rie in the pages of influential architectural magazines like Domus. In England she had contact with Rie, as well as with the work of the artists Nicholas Vergette and Hans Coper, and it was Coper’s work in particular that deeply informed Gazzard’s ceramics on her return to Australia in 1960.

At the time, only a few Australian potters were experimenting with forms beyond the purely functional. It is true that many potters had made smaller scale sculptural pieces – John Percival’s famous Angel works are a good example – but it is a mistake to confuse this work with ceramics which have a more direct connection to architecture.

These connections are sometimes obvious, as in the incorporation of ceramics into a building or

its surrounds; at other times they are more indirect. Sometimes it is just a question of scale, as when the Austrian-born sculptor Bert Flugelman collaborated with Les Blakebrough on large scale ceramic sculptures that were made and subsequently exhibited at the Sturt Workshops in Mittagong. To pick a more contemporary example, Deborah Halpern’s well-known artwork Angel (not to be confused with the Percival ones), originally sited at the entrance to the National Gallery of Victoria and now found

at Birrarung Marr park on the banks of the Yarra River, is architectural in nature not only because of

its scale but through its intent, in that it was commissioned to be a part of a building or its immediate surrounds. This is seen quite literally in the visual pun of the sculptor Aleks Danko’s, Songs of Australia Volume 3, At Home sited in the courtyard facing the JamFactory Craft and Design Centre, the Experimental Art Foundation and the entrance to UniSA’s City West Campus in Adelaide.”

It seems likely that the emphasis has shifted in contemporary architectural ceramics in Australia, from large-scale public commissions to community-based projects. However, given the obdurate nature of the material and its intrinsic connections to the built environment, ceramics will probably always find some place in the architecture of the day.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

- I feel it is reasonable to claim Romaldo Guirgola as Australian since, although he was born and trained in Italy and has spent much time living in America, he took up Australian citizenship in the 1980s.

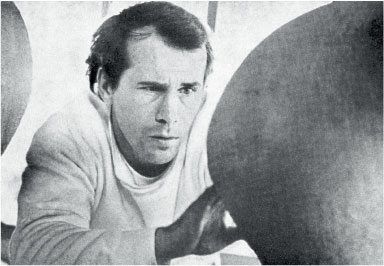

The Flying Scotsman

The last time Alex Leckie’s name was mentioned in dispatches, prior to news of his passing earlier this year, was in relation to the proposal in 2008 to close the ceramics department of the Glasgow School of Art.

Leckie’s name was inextricably linked to this institution. It was where he had begun studying in 1950 when, as the then Academic Registrar (Sir) Harry Barnes would later recollect, he was admitted ‘by the back door’, having shown a great deal of promise but possessing none of the normal qualifications to gain entry.1

It is unsurprising that the young Alex Leckie didn’t take to the disciplines of the post-war British education system, given his rather idiosyncratic upbringing. His father was an ardent communist and political activist who, nonetheless, instilled an appreciation of the arts into his son. The Leckie household library was extensive, containing several thousand books, and there were visits to art galleries and museums where he developed his appreciation of the work of ancient cultures, echoes of which would be found in his own ceramics in later years.

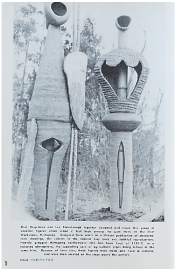

Leckie excelled at art school and was offered the chance to complete a Post-Graduate Diploma. A figurative vessel that was exhibited in that graduation exhibition is illustrated here, and demonstrates both his command of the medium and a remarkably early adoption of what would later become recognisable as his mature style.

In 1955, and in imminent danger of being called up for National Service, Leckie decided to move to Australia. Having relatives in South Australia he settled in Adelaide where he soon found employment throwing garden pots at Bennetts Magill Pottery, a job which he would later describe as providing ‘good discipline’.2 Enquiries at the South Australian School of Art led him to discover that he was the most highly qualified potter in South Australia, a situation which, rather ironically given his background, led to him being employed in 1956 as a teacher of ‘pottery and sculpture’.

It’s worth pausing at this stage to place Alex Leckie in the context of the early world of post-war Australian ceramics. When Leckie arrived in Australia, Ivan McMeekin, Ivan Englund, Peter Rushforth and Mollie Douglas were just establishing the Potters’ Society of NSW, Gwyn John (Hanssen Pigott) was still apprenticed to McMeekin at Sturt, Carl McConnell was active in Brisbane, Henri Le Grand was teaching in Canberra, Harold Hughan and members of the Boyd clan were taking their varying approaches to ceramics in Victoria, and there certainly were others – but not that many.

Considering where to place Leckie in this field is an interesting exercise. For a start, he was not a single-minded devotee of the Anglo Oriental approach espoused by Leach and Cardew, instead showing a preference for a modernist, European sensibility which brings to mind Picasso’s anthropomorphic ceramics. But Leckie also didn’t favour the rather commercial, high-keyed palette of earthenware, his surfaces instead relying on the subdued colours of clays and ochres, albeit enlivened by his use of colour and a marvellously dexterous feel for line and modelling. His ceramics refer back to the archaic forms which inspired him in his youth, where man and beast, male and female, entwine and merge in a sensuous dance with the medium of clay.

For all his undoubted technical and artistic abilities and a myriad of friends and supporters within the arts community, Leckie’s rebellious nature ensured that his tenure within the South Australian education department would not be without problems.

The by now well-known episode of Leckie swimming naked in the River Torrens and of his subsequent arrest (a seemingly trifling incident which provided front page titillation for the tabloid press and ultimately led to Leckie’s dismissal from his teaching post in 1962), introduced a surprisingly productive period during which he exhibited widely, undertaking many important commissions and becoming President of the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia. In 1964, he was one of three Australian ceramicists chosen to represent this country in the International Ceramics Exhibition in Tokyo, with his work, Destroyed City also appearing on the cover of Pottery in Australia. 3 4

In 1966, Alex Leckie decided to return to Britain. He spent a short time in London at the Central School of Art before returning to Scotland, where he was appointed Head of Ceramics at the Glasgow School of Art in 1968, a position he held for the next twenty years.

In an obituary published in The Scotsman, Jimmie Macgregor wrote that Alex Leckie ‘ ... took a moribund ceramics department by the scruff of the neck, completely transforming it and turning out students who were a credit to the school.’5

In all fairness, the Glasgow School of Art probably deserves considerable credit for keeping Leckie on staff for twenty years, as this ‘... wee bull who caused havoc in many a china shop ...’6 would certainly find difficulty adapting to today’s more politically correct academic setting. No more would a whole pig be roasted in the kiln as a contribution to Activities Week, but perhaps the managerial class which now largely controls the directions of art schools, on either side of the world, will doubtless rest easier at night.

When he left this country in 1966, Leckie was as well-credentialled as anyone, exhibiting nationally in prestigious galleries, working on architectural commissions and, above all, selling large amounts of his work to an appreciative public, all of which he achieved by the age of 35. He left behind many admirers, fond memories, some scandalous tales and an engaging and highly accomplished body of work. It is

to be hoped that an opportunity might exist in the not too distant future for the current generation of Australian ceramicists to be able to see a comprehensive exhibition of the work of Alex Leckie.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

- ‘Alex Leckie Ceramics’, an essay by Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes accompanying an exhibition at the St Enoch Exhibition Centre, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery.

- Ceramics in South Australia 1836 – 1986; from folk to studio pottery, Noris Ioannou

- Destroyed City by Alex Leckie, cover image, Pottery in Australia, Vol.3 No.2., October, 1964.

- In the end, four Australian potters were included in the International Exhibition of Ceramic Art in Tokyo – Alex Leckie, Milton Moon and Bernard Sahm were chosen by the various Australian selectors, whilst the Canberra-based potter Cecily Gibson was included following her extended residency in Japan.

- Appreciation: Alex Leckie, Jimmie Macgregor, The Scotsman, 12 February 2010

- ibid

Bennetts Magill Pottery Pty Ltd – a living history

Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

Currently in its fifth generation of family ownership, Bennetts Magill Pottery in Adelaide provides one of the last remaining glimpses into the small- to medium-size manufactory that was the mainstay of Australian ceramics throughout the nineteenth and into the first part of the twentieth century.

The founder, Charles (Chas) Bennett, was born in Somersetshire in England in 1842. In 1849 he travelled with his family to the newly established colony of South Australia, settling in Magill, then a semi-rural area a few miles east of the centre of Adelaide. Good supplies of clay, as well as abundant fuel in the shape of the string-bark forests cladding the adjacent hills, ensured the area quickly became home to a number of potteries, established to fulfil the needs of a rapidly growing population.

Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

The young Charles Bennett gained an apprenticeship at just such a pottery, run by a Cornish immigrant, third-generation potter named John Henry Trewenack. From the age of twelve, Bennett worked at Trewenack’s, first as an apprentice then as a full employee, where he spent many years learning about all aspects of the craft. In 1883, Charles Bennett, together with his son, William Charles Bennett, worked for a time at the nearby Piercy brothers pottery and it was there that the young William Bennett met his future wife, Abigail Piercy, forming a union that perhaps ensured the future importance of ceramics to the Bennett’s clan. Clay, it seems, was in their blood.

photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

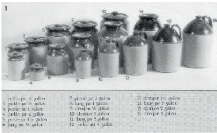

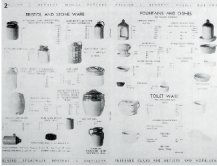

Following the death of William Piercy in 1885, the business went into decline, prompting the Bennetts to finally establish their own pottery on land the family owned at Magill. The pottery started trading at a date towards the end of the 1880s (the actual date is given variously between 1887 and 1890). Initially consisting of a shed, a horse-drawn pugmill and a small wood-fired kiln, the Magill Pottery Works, as it was called then, was gradually expanded to include a bottle-kiln, larger workshops and some mechanisation in the shape of steam or oil driven engines, thus relieving the horse of its more burdensome duties. Further equipment was added with the purchase of new throwing wheels manufactured by the English company of William Boulton Ltd, by which stage the pottery, now called C. Bennett and Sons, was producing a vast range of the kind of useful, no-nonsense pottery needed by homes, farms and industry – bread crocks and mixing bowls, preserving jars, acid, wine and spirit jars, butter coolers, poultry waterers, and garden and chimney pots.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the pottery, now under the management of William Bennett, continued to increase the range of goods on offer. In addition to an assortment of terracotta pots there were several types of glazed domestic wares, although, in keeping with the mainstream of Australian ceramic practice, no fine dinnerware was produced, this market being met by imported English ceramics. Further to this, a range of highly successful ‘art pottery’ was produced, with vases and other decorative items being glazed in a variety of mottled and streaked lead-based colours, often referred to as Majolica or agate wares.

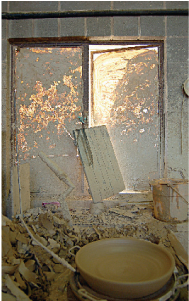

photo: Damon Moon

There were, however, setbacks. On the morning of 27 November 1940, a fire razed the building to the ground, leaving a total damage bill of around ten thousand pounds. The pottery was rebuilt, but by the time an official of the Department of Mines visited the factory in 1946, the pottery had returned to its core production, where:

Bennett’s products are largely confined to a stoneware and coarse domestic ware. Acid jars are thrown on the wheel ... Bristol ware is ... [made] ... from Tea Tree Gully clay with some Woocalla ball clay added to extend the vitrification range.1

By 1950 the pottery was being run on a day to day basis by the third-generation William Reginald Bennett. The kilns were now fuelled by oil, which, unfortunately, did not prevent a second massive fire from destroying the pottery in 1956. Reginald Bennett seriously considered whether to rebuild the pottery, but since his own son, Robert William Bennett, was now working at there, it was decided that the business would continue.

In 1964, Robert assumed control, in a marketplace where conditions were changing rapidly. Although the majority of garden wares used in Australia were still produced locally, the lifting of post-war restrictions had allowed an ever greater amount of imported ceramics to enter the market, a move which led to the demise of many of the small manufactories which had sprung up in the immediate post-war years. Bennett’s responded to this decline by diversifying their manufacturing base, for a time even supplying bricks to a booming building industry, but also, conversely, by sticking to their guns and continuing to make a range of utilitarian pots almost identical to those they made in the late nineteenth century. A growth of interest in the crafts throughout the 1970s saw these traditional pots come back into fashion, while the proliferation of ceramics courses and increasing numbers of practitioners provided a ready market for Bennett’s clay. With the closure of Koster’s Pottery in 1977, Bennett’s was left as the sole South Australian pottery operating along more or less traditional lines.

In the mid-1970s, Robert’s son, John William Bennett, became the fifth generation to work at the pottery, and he now runs the business in a family lineage that spans three centuries. The last twenty or so years have seen added pressure on the business from imported garden wares, but Bennetts endures, providing a fascinating link to the vernacular ceramic traditions of the past.

Photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

A Family Affair – the Boyds and the History of Australian Ceramics

If Australia can lay claim to having an artistic dynasty, it is to be found in the Boyds. This country has produced many worthy artists but there is no other family that can boast members who rose to prominence in the fields of painting, literature, architecture and ceramics, and did so over several generations.

It is well known that many of the Boyds made ceramics, but what is unusual is the depth of their familial or collective involvement and the way ceramics were seamlessly integrated into a life of rich artistic endeavour. The Boyd’s involvement in the arts can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, to Arthur Merric Boyd snr and Emma Minnie Boyd1, both accomplished painters who had studied at the Royal College of Art in London. They had three children: Martin, who would become a well-known novelist, Penleigh, who was hailed as one of Australia’s most promising young painters until his untimely death in 1931, and William Merric, who would become the first Australian artist potter.

As a young man, William Merric Boyd (who is generally just known as Merric Boyd) studied art at the National Gallery School in Melbourne. Legend has it that during a trip to a commercial pottery to buy modelling clay for a sculpture class he was asked if he would like to try his hand at throwing a pot. It is recorded that he threw a perfect pot at his first attempt, an event that has undoubtedly been subject to exaggeration over the years, but nonetheless points to an early affinity for the medium of clay.2 Merric Boyd decided to become an ‘art potter’, working from a studio on a block of land the family purchased for him at Murrumbeena, a suburb then on the semi-rural outskirts of Melbourne. In 1912 Merric Boyd became a part of ceramic history by holding the first one-person exhibition of pottery in Australia at Centreway, a gallery in Collins Street in Melbourne. In 1915 he married Doris Gough, a fellow student from the National Gallery School, and she went on to work closely with Merric Boyd, decorating many of his ceramics over the subsequent years. By the time Merric Boyd left Australia in 1917 to fight in the First World War he was already a well-known ceramic artist.

Following his discharge from the army in England in 1918, he spent a year studying at the Wedgwood factory in Stoke-on-Trent, financed by a Commonwealth Rehabilitation Grant. On his return to Australia he resumed work at Murrumbeena where his ceramics met with considerable success. In keeping with the times he worked in earthenware, throwing pots which were then heavily modelled and decorated – often by Doris Boyd – in a faux-naïve style replete with references to Australian plants and animals. Although he was sometimes able to sell work for considerable sums, his financial position was always somewhat precarious (no surprises there), leaving the Boyds and their growing family living in ‘an indefinable, vaguely Boehemian style of artistic poverty.’3

All of Merric and Doris Boyd’s children – Lucy, Arthur, Guy, David and Mary – learned the elements of pottery at an early age, helping out in the family business. Following the end of the Second World War the pottery entered a new phase, with the young Arthur (Merric Bloomfield) Boyd, in partnership with his colleague and friend John Perceval4, establishing a new workshop next to the now disused Open Country pottery, which they named after Arthur’s grandfather, calling it the Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery. Together with the Viennese émigré Peter Herbst5, they manufactured goods for the Ministry of Labour and National Service, as well as making individual art pieces.

During the 1940s, the Boyds’ encampment at Murrumbeena became a haven not only for the family but also their friends, ‘becoming more and more a loose colony of artists and intellectuals – one of the very few enclaves ... to offer protection to radical modernists.’6 A similar group of artists gathered around John and Sunday Reed at Heide, a farmhouse located in the outlying Melbourne suburb of Heidelberg. There was some interaction between the two groups, with the artists Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester7, all names closely associated with Heide, visiting the Boyds at Murrumbeena. In addition, many figures who would go on to be well-known figures in Australian ceramics worked at or at least had contact with the Boyd workshops, including Carl Cooper, Tom Sanders and Hatton Beck.

David Boyd, who was a talented pianist, initially studied music at the Melbourne Conservatorium. In 1945, following his military service, he transferred his Commonwealth Retraining Grant to the National Gallery School where, following in his parents and grandparents footsteps, he embarked on a career in the visual arts. Studying drawing under the famous but rather conservative artist and teacher Sir William Dargie, Boyd soon rebelled. He moved to Sydney where one of his brothers, Guy, had already re-located in order to study sculpture at the National Art School with Lyndon Dadswell. During 1946 the two brothers became involved in a pottery enterprise, with David making a final move to Sydney in 1947. The colourful, popular ware they made was sold under the name of Martin Boyd Pottery, again following a confusing family tradition of naming workshops after members of the family who actually have no ties to the business being conducted, in this case David’s expatriate novelist uncle.

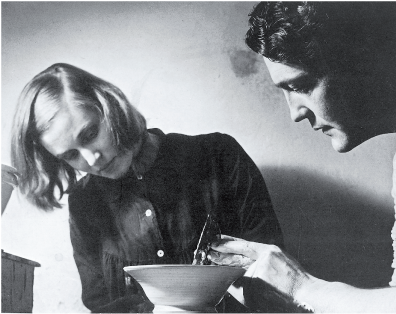

In the period between David’s initial contact with the business in 1946 and his return to Sydney in 1947, Guy had employed several fellow students from the National Art School to help in the workshop. One of these was Hermia Lloyd-Jones, a young and precociously talented artist who came from a family background that bore some similarities to that of the Boyds.

David and Hermia soon became a couple in life as well as in ceramics. In addition to the successful commercial ware, they began work on a group of ceramics primarily intended for exhibition and, in 1949, these works were shown at the Little Gallery at the David Jones department store. The Daily Telegraph’s art critic wrote:

‘It is rare to find produced in this country works of art which may, in both technical and aesthetic achievement, be judged by world standards. In the pottery of David and Hermia Boyd, that distinction is reached ... It is a show not to be missed by collectors and those who are interested in the beginning of an epoch in Australian art.’8

In 1950, David and Hermia Boyd, as so many other Australian artists had done before them, travelled to England. Having obtained a licence to sell their pottery from the Board of Trade, issued9 through the Crafts Council of Great Britain, they soon found a ready market for their pottery in many fashionable London outlets. The British trade journals Pottery and Glass and Pottery Gazette featured their work, as did several lifestyle magazines and they were able to obtain a lucrative licence to produce items for the 1951 Festival of Britain.

During this period the Boyds also spent a year in France, making pottery in the small village of Tourrettes-sur-Loup, positioned midway between Cannes and Nice in Provence. Returning to England, the Boyd’s resumed potting, including an exhibition at the Barling’s gallery in Mayfair and a stint designing work for the resurrected Chelsea Pottery, but, following a particularly cold English winter, they felt the urge to return to Australia. After rushing to fulfil a final order for Heals department store – worth around £3000, a very large sum of money for the time – the potters ‘returned in triumph to their homeland’.10

The Boyd’s successes abroad had been closely followed by the Australian press and their homecoming was accompanied by a blaze of publicity, or at least as much publicity as might reasonably be accorded to a pair of potters. The first exhibition held on their return, again at the Little Gallery at David Jones department store, was favourably reviewed, with The Herald’s art critic, Alan McCulloch, reporting that the pottery was ‘quite exquisite in design, shape and finish, and in fact much superior to anything of the kind that has so far been shown here.’11

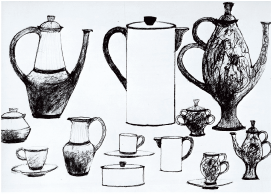

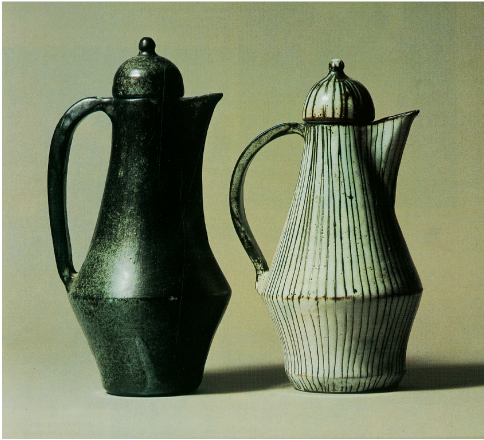

Over the next five years, David and Hermia Boyd continued to have regular sell-out exhibitions in the major cities, extending their formal language based on high-fired earthenware, original forms and decorations based on a marvellously fluent graphic sensibility and an extensive use of oxides (in particular manganese and copper) applied over or inlaid into commercial glazes.

At this point, in the mid to late 1950s, the stoneware pottery movement was in its formative stage with Harold Hughan in Melbourne and Ivan McMeekin and Peter Rushforth in New South Wales. By contrast, David and Hermia Boyd had around fifteen years of highly successful, innovative and lucrative ceramic practice behind them in England, France and Australia, with a string of sell-out shows meeting with critical acclaim, and involvement in commercial enterprises that had sold thousands of pieces of pottery. They were so far ahead of the game it’s difficult to see how, within another few years, they would be almost overlooked by the burgeoning Australian ceramics movement, and yet that is precisely what occurred.

Partly, this is because they decided to return to Europe in early 1962, following the awarding of an Italian government painting prize to David, who was increasingly concentrating on sculpture and painting as expressive mediums. At the end of this year the Boyds returned to England, where they would remain for much of the 1960s, and although they would continue to make ceramics to supplement their other artistic interests, their contribution to Australian ceramic life was effectively resigned to history.

Another reason David and Hermia Boyd’s contribution to Australian ceramics was overlooked was simply because they had worked exclusively in earthenware, when the orthodoxy of Leach-inspired Anglo Oriental ceramics was at its zenith. Colourful, earthenware ceramics, no matter how well done, were deemed to be old-fashioned, crass even, by the exponents of Antipodean Sung, who somehow overlooked Leach’s own enthusiasm for English slip-wares, which of course were also earthenware. For their part, David and Hermia Boyd held similar prejudices, having seen and dismissed much of British studio ceramics in the 1950s as being rather amateurish essays in a ‘recently evolved tradition’12,

with Hermia remarking on the preponderance of ‘Japanese squiggles or the Leach-introduced Eastern hieraglyphic [sic] for ripening corn’.13

Therefore, when the journal Pottery in Australia was first published in May 1962, with editor Wanda Garnsey taking pains to ‘acknowledge the stimulus of Bernard Leach’s personality ... following his visit to Sydney’14, it’s hardly surprising that the recent, spectacular contribution of two generations of Boyds would be ignored, as indeed it was for many years to come. It is therefore entirely fitting that this article appears in the successor publication to Pottery in Australia and I can only hope that the contribution of the Boyds, and in particular that of David and Hermia Boyd, is re-assessed and appreciated by a new generation of Australian ceramic artists.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2009

- Emma Minnie Boyd nee a’Beckett, daughter of the first Chief Justice of Victoria, Sir William a’Beckett.

- Vader, J, p.18

- Niall, B, The Boyds: a family biography, Melbourne University Press, 2002

- Both Arthur Boyd and John Perceval went on to become very well-known and respected painters.

- Herbst went on to become Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National University and a founder of the Humanities Research Centre.

- Cochrane p. 70

- Sir Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester all become well-known painters. Sidney Nolan was also married to Mary Boyd.

- Vader, J p.27

- The Boyds’ licence to trade was issued by the Crafts Council of Great Britain against the wishes of its Director, the potter Heber Mathews. For a revealing glimpse into post-war British craft politics, see Vader, J, pp. 37–39

- ibid p. 107

- ibid p. 113,114

- ibid p. 36

- ibid p. 37

- Garnsey, Wanda, Editorial, Pottery in Australia, Vol. 1 No. 1, 1962

And then came Funk

Introduction

This is an essay about the introduction of funk ceramics into Australia and the affinity this work found in the social, artistic and political environment of Adelaide in the late 1960s and 1970s.

For those not familiar with the term, funk ceramics describes sculptural work that combines a Pop Art sensibility with the history of ceramics as a decorative art. At its inception it could even lay claim to being a regional art form, centred around San Francisco, where its iconoclastic, stoner style drew on the street culture, comics and band posters of early hippydom, as well as finding a parallel in the work of fine artists like Ed Kienholz, William Wiley, Claes Oldenburg, Billy Al Bengston and Robert Rauschenberg.

Arriving in Australia at the end of the 1960s funk adapted to local conditions, morphing into the idiosyncratically titled ‘Skangaroovian Funk’, a term derived from ‘Skangaroovia’, which (believe it or not) was an alternative name for South Australia suggested by Daniel Thomas, Director of Art Gallery of South Australia from 1984 to 1990. The title was then retrospectively applied to this ceramics movement in a small, but important, survey exhibition, curated by Judith Thompson, at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1986.

The grungy, low-tech feel of San Franciscan funk was soon left behind as these new ceramics became sleeker and more theatrical, an approach epitomised in the politically and sexually charged ‘porcelain confection[s]’ of Adelaide artist Mark Thompson.

There surely have been few Australian ceramic movements which echoed so perfectly the artistic and social temperament of a time and place as Skangaroovian Funk did so for Adelaide in the 1970s. Funk was the contemporary Medici porcelain for a city that the sculptor Bert Flugelman had christened “Florence on the Torrens”, a play on Adelaide’s nickname as the “Athens of the South”. Skangaroovian Funk was variously decorative, political, inventive, daggy, provocative, impressively-crafted and camp as a row of tents.

Although looming large in the annals of South Australian art history, this period is not necessarily a comfortable place to revisit, but it is always instructive to reacquaint oneself with the avant-garde, if only to see how it has aged.

Origins

The word ‘funk’ has several meanings. One, not used much anymore, is to be frightened of something or to show cowardice. English speakers would say they were ‘in a funk’ if they were sulking or frightened or otherwise out of sorts.

In America, funky is a colloquial expression for something that smells or tastes bad, although the term is also slang for the taste and smell of sex. This usage is still apparent today, as when the character Samantha on the series Sex and the City complains about … oh, never mind.

Funky also suggests a kind of fashionable but casual style (maybe the newest incarnation of this is the ‘hipster’) but by far the most common use of the word is in the context of funk music ‘… an up-tempo style of … music originating on the west coast of America …’, and then there is also funk-art, ‘… a style of art originating on the west coast of America which reacted against the more rigid New York style of abstract expressionism … a regional variant of pop art.’

It’s certainly true that funk art never set out to be classically beautiful or well-crafted, grand, weighty or profound. It set the bar lower than pop and then slid right on under, mating the cartoon-like, flaccid-fakery of Claes Oldenburg’s soft sculpture to the low art forms of advertising, underground comics and the detritus of street life.

Born in San Francisco, funk was officially christened by the writer and curator Peter Selz and the artist Harold Paris in two 1967 articles for Art in America; Selz’s ‘Funk Art’ and the evocatively titled companion essay from Paris, ‘Sweet Land of Funk’, both of which appeared under the single title ‘West Coast Report: Funk Art’. Peter Selz, in his 1985 review of Thomas Albright’s book Art in the San Francisco Bay Area 1945 – 1980, noted that all throughout the 1950s and 1960s West Coast artists felt that they were working outside of the mainstream

‘… artists were willing to take greater chances … they dwelled in … the “Sweet Land of Funk”. The artist … is aware that no one really supports the work. So, in effect, he says Funk!’

Introducing ceramics into the equation, Selz goes on to write that

‘It was in the Bay Area that Peter Voulkos and his extraordinary group of disciples raised ceramics to the non-utilitarian, i.e. aesthetic sphere … at the very time when New York critics, painters and collectors under the tutelage of Clement Greenberg extolled the sanctity of the flat surface.’

This is not quite right, in that Volkous had already reconfigured ceramics in the spirit of abstract expressionism during the years he spent at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (later renamed the Otis Art Institute) from 1954 to 1959. This initial revolution was therefore Southern Californian and centred around Los Angeles, not San Francisco.

Collette Chattopadhay, in her article for Sculpture Magazine, quotes Voulkos as saying that ‘” … there was a certain energy around L.A. at the time …” … The laissez-faire characteristic of the city, without the expectant pressures of gallery shows and sales, granted time, space, and an artistic permission that was intrinsic to the clay revolution.’

If Voulkos, the budding demigod of American ceramics, was responsible for bringing the macho energy and physicality of abstract expressionism to clay, the origins of funk can also be traced fairly accurately.

In 1961 Robert Arneson was teaching craft and design at Mills College in Oakland, California, just across the bay from San Francisco. ‘While demonstrating throwing a pot at the Sacremento State Fair, Arneson topped a small, traditionally thrown bottle with a bottle cap and added the text “No Deposit, No Return”,’ in a comic and subversive gesture that would later resonate as powerfully through the ceramics community as the grandiloquent statements of Peter Voulkos or the hybrid Anglo Oriental style espoused by Bernard Leach.

Later that year, Arneson was appointed to teach ceramics at the University of California’s Davis campus on the outskirts of San Francisco. Although the art department was relatively new, this didn’t extend to the building in which Arneson found himself; a long, low structure which had variously been used as the campus post office, police station and as a store for experimental canned and packaged foodstuffs. This humble building, known as TB9

(Temporary Building Nine), would provide the setting for a generational shift in style which would echo around the art world, or at least the relatively small part of the art world that concerned itself with ceramics.

Arneson recognized that despite - or maybe even because of - the lack of facilities or long tradition, Davis was a place where he could do exactly what he wanted, so he set about creating a ceramics department where experimentation was not just encouraged but demanded, where …’Anarchy reigned. No overwhelming structure or “curriculum” … hamper[ed] … your creative flow. … Bob just sort of sat back and let it all happen.’

Arneson soon achieved notoriety when, given the chance to exhibit with Voulkos and John Mason in a show called California Sculpture curated by John Coplans at the Kaiser Centre in Oakland, he decided to make a toilet.

‘I cut myself loose and let every scatological notation in my mind freely flow across the surface of that toilet.’

The work, originally titled Toilet and re-named Funk John about two years later, was removed from the exhibition, following objections expressed by the Vice President of Kaiser Industries [ … no, I’m not making this up …] that the piece …’ attack[ed] American capitalism …’ an interesting notion given the strong symbolic relationship between shit and money, not to mention the subsequent high value of Arneson’s work on the secondary market.

Following on from Duchamp’s seminal Fountain of 1917 and Arneson’s Toilet, it’s a pity that no one has managed to cause offence with a bidet, thus completing a trifecta of art historical controversy in sanitary ware.

Arneson had many talented students in the early days at Davis. Bruce Nauman would go on to be one of the most important conceptual artists of the last quarter of the twentieth century. There was also David Gilhooly, one of Arneson’s first students who himself became a teacher, and who continued to be associated with Davis and the Funk ceramics movement for several decades. In fact, the roll call of early students reads like a who’s who of Funk ceramics; Chris Unterseher, Stephen Kaltenbach, Peter Vandenberge, Seymour Howard, Roy de Forest, Richard Notkin, but there was one student in particular who provided the connection between what was seen to be the cutting edge of American ceramics and Adelaide in the late 1960s, and that person was Margaret (Helen) Dodd.

The South Australian Connection

Dodd had arrived in California on the Fourth of July, 1965 in the middle of a heatwave, not exactly unfamiliar weather for a South Australian, albeit at a strange time of year. She had originally studied at the South Australian School of Art and worked for four years as an art teacher before travelling to the USA, where, after several moves, her husband had gained employment in the University of California’s physics department at the Davis campus. Given her status as a ‘faculty wife’ Dodd could audit or sit in on subjects without being formally enrolled. She initially chose to study sculpture and so found herself working in TB9, since that building housed both the sculpture and ceramics facilities

At first Dodd studied a range of different techniques, working with metal and wood as well as making wheel-thrown pottery, but it was during a ceramic sculpture course with Arneson she was set an assignment to make a ‘double illusion’, thus initiating a course of work that would last up to the present day. Dodd had recently seen the American artist Dennis Openheim’s work Funk Truck, a cab-truck shape in foam rubber on a wood core and covered with polka dot and leopard skin fabric. She took the idea one step further and made a Fake Funk Truck out of clay, a piece which certainly qualified as a double illusion, and then some. Even the title was in keeping with the spirit of funk, where punning was all the rage and the idea of the ‘fake’ was gaining an artistic and theoretical credibility, a concept aligned with pop art and quite at odds with the basic theoretical tenets of the movement that preceded it, that of abstract expressionism.

In 1966 Dodd formally enrolled in the ceramics course, where she continued to make ceramic automobiles; ‘Buicks, Oldsmobiles, Cadillacs … and a “run of VWs, beetles and buses”’ work that was readily accepted by her peers and that placed her at the centre of American funk ceramics. Her work was included in important exhibitions, including the 1966 survey show Ceramics from Davis, put on by the American Craftsmen’s Council at the Museum West Gallery in San Francisco.

Given her involvement in an exciting new ceramics movement that was quickly gaining critical momentum, it was with some reluctance that Dodd faced the prospect of returning to Adelaide, again following her husband’s academic career. Soon after her graduation from Davis in 1967 she found herself living in the Adelaide suburb of Holden Hill, where, according to Judith Thompson, ‘…pregnant and with time to herself, she found she had time to reflect on the experiences of being a woman in Australia’.

Nonetheless, she was back in her home town and, artistically-speaking, she had to make the best of it. Drawing on her experiences of California funk, feminism, Australian automotive history and (perhaps subliminally) childhood memories of her father’s stint as a car salesman with Wakefield Motors, Dodd started to make a body of work that would ensure her place as the icon - or perhaps the hood ornament - of Australian funk.

Skangaroovia – it’s our state, mate!

The environment Dodd found herself in was not entirely philistine. South Australia was undergoing a kind of cultural renaissance, due in part to the artistic leanings of the newly appointed Premier, Don Dunstan. In the days when very few cities actually had festivals, the Adelaide Festival of Arts had an international standing. There was also the South Australian School of Art, an institution with a history dating back to 1856, its own purpose built premises on the fringes of the city and an eclectic mix of staff, many of whom had at least a passing interest in ceramics.

In 1963 the American ceramist Ben Kypridakis took over the teaching of ceramics in the new art school building in Stanley Street, North Adelaide, but it wasn’t really until the arrival of the British artist Bill Gregory in 1966 that a Pop sensibility began to creep into South Australian ceramics. Gregory sought to

‘…break down the conventional concepts of ceramics held by staff and students. Functional ceramics did not interest him … Instead, he was interested in an intellectual or object-making approach to ceramics. He devised a set of exercises, designed to develop “conceptual attitudes” in his students …’.

No one came up with a ‘fake funk truck’ in response to his methodologies, but they could well have done. Gregory’s own ceramics, according to Patrick McCaughey’s review of his 1968 exhibition at the prestigious Pinacotheca gallery in Melbourne, were ‘ … splendidly hideous and marvellously useless, taking the mickey out of Arts and Crafts pottery … ‘.

Or, to quote Donald Brook

‘There are far few spectator sports more agreeable than watching someone stride up to a holy cow and kick it in the slats so shrewdly that the sawdust dribbles out. Studio pottery is just such a sacred animal, and Bill Gregory … is the man with the deft boot … his pots are absolutely useless … as refreshing as drought-breaking rain after an aeon of cider jugs with bucolic bodies like boiled oatmeal and orchid jars in a sensitive toffee temmoku.’

One begins to sense a pattern here in the critical reception of funk, at least amongst a group of curators and theorists for whom the positioning of functional pottery within the fine arts had always been problematic.

During this period there were other artists, many of whom were involved with the South Australian School of Art, either as students or teachers, who took a somewhat unorthodox approach to clay.

One such person was Bill Clements, a sculptor who had lived and studied in Japan from 1964 to 1967, arriving at the South Australian School of Art in 1968. Clements worked in a variety of mediums, but clay always played a central part in his practice, where his observations of the avant-garde Japanese ceramics movement brought an entirely different sensibility to that normally associated with Japanese pottery. Another was Ian Smith, who used traditional techniques such as wood-firing in a very non-traditional manner, as in his 1968 work The Generals which commented on the Vietnam War. Ron Rowe made ceramic objects inspired by machine parts and Aleks Danko, a young and precociously talented sculpture student, made several early works in ceramics, amongst which his series of ‘shoes’ and ‘numbers’, circa 1969, clearly showed the influence of Bay Area funk in their bright colours, offhand modelling and a kind of un-sophisticated or even slightly childish inventiveness.

Another student from the art school, Jim Cowley, exhibited a series of Shrines at the Llewellyn Gallery in 1971, the same year that Olive Bishop began working privately with Dodd at her College Park studio. Whereas Dodd had chosen the automobile as the appropriate vehicle to convey her ideas, Bishop fixed on the motif of the shirt and coat. She is perhaps best-known for her Wash and War series of ceramic shirts, based on uniforms emblazoned with medals (literally decorations) that parodied militarism, particularly in the context of the Vietnam War.

In 1969 Milton Moon had been appointed senior lecturer in charge of the ceramics department of the South Australian School of Art. He combined a commitment to traditional workshop skills with a personal body of work that, although often exploring the formal boundaries of pottery, remained philosophically based in the modernist tenets that had informed the development of ceramics within the crafts movement. At that time, Moon was deeply interested in traditional Japanese ceramics and in exploring the origins of the aesthetic philosophy that had informed their development. Many of his students revelled in this learning environment, but some did not.

Mark Thompson was one of the latter. Previously a student at the National Art School in Sydney, in 1973 Thompson enrolled in the Diploma of Painting at the South Australian School of Art. Although during this year he spent much of his time in the ceramics department he was not formally considered a student of the department and therefore was free to pursue his own directions in clay as an extension of his painting practice.

Moon spent the following year studying in Japan and it was during this time that students like Mark Thompson (who was now formally enrolled in the ceramics course) and fellow student Paul Greenaway, together with artists such as Margaret Dodd, Olive Bishop and Bruce Nuske (an ex-student of Moon’s who had graduated in 1972) were finding that their irreverent and satirical take on ceramics was becoming an accepted part of mainstream Australian crafts practice.

Thompson’s work began to make extensive use of dolls, moulded and cast in white earthenware clay or in porcelain. Highly finished and precise, one gets a sense that the original devil-may-care ‘Funk!’ attitude of Arneson and his followers had been replaced with a very calculating approach, one that left nothing to chance. His ‘China Cabinet Objects’ show Thompson using his already formidable skills in painting and modelling to draw on the history of industrially produced ceramic sculpture, which he then parodies to create objects that are quite literally inverted and made strange. For example, a rather trite, traditional sculpture depicting a child sitting amidst a cornucopia of fruit is subverted by turning the infant on its head, so that one sees a pair of legs pointing skywards, pinned between a couple of ceramic bananas and a pear. Beautifully done, and amusing enough in its own way, but really no more profound than the work it parodied. Thompson, however, was just getting started.

His 1976 Jam Factory Gallery exhibition Ceramics and Porcelain Dolls must have been amongst the very first ceramics exhibitions in Australia to delve into the realms of installation art, where entire sections of the gallery space became an integral part of the work.