If Australia can lay claim to having an artistic dynasty, it is to be found in the Boyds. This country has produced many worthy artists but there is no other family that can boast members who rose to prominence in the fields of painting, literature, architecture and ceramics, and did so over several generations.

It is well known that many of the Boyds made ceramics, but what is unusual is the depth of their familial or collective involvement and the way ceramics were seamlessly integrated into a life of rich artistic endeavour. The Boyd’s involvement in the arts can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, to Arthur Merric Boyd snr and Emma Minnie Boyd1, both accomplished painters who had studied at the Royal College of Art in London. They had three children: Martin, who would become a well-known novelist, Penleigh, who was hailed as one of Australia’s most promising young painters until his untimely death in 1931, and William Merric, who would become the first Australian artist potter.

As a young man, William Merric Boyd (who is generally just known as Merric Boyd) studied art at the National Gallery School in Melbourne. Legend has it that during a trip to a commercial pottery to buy modelling clay for a sculpture class he was asked if he would like to try his hand at throwing a pot. It is recorded that he threw a perfect pot at his first attempt, an event that has undoubtedly been subject to exaggeration over the years, but nonetheless points to an early affinity for the medium of clay.2 Merric Boyd decided to become an ‘art potter’, working from a studio on a block of land the family purchased for him at Murrumbeena, a suburb then on the semi-rural outskirts of Melbourne. In 1912 Merric Boyd became a part of ceramic history by holding the first one-person exhibition of pottery in Australia at Centreway, a gallery in Collins Street in Melbourne. In 1915 he married Doris Gough, a fellow student from the National Gallery School, and she went on to work closely with Merric Boyd, decorating many of his ceramics over the subsequent years. By the time Merric Boyd left Australia in 1917 to fight in the First World War he was already a well-known ceramic artist.

Following his discharge from the army in England in 1918, he spent a year studying at the Wedgwood factory in Stoke-on-Trent, financed by a Commonwealth Rehabilitation Grant. On his return to Australia he resumed work at Murrumbeena where his ceramics met with considerable success. In keeping with the times he worked in earthenware, throwing pots which were then heavily modelled and decorated – often by Doris Boyd – in a faux-naïve style replete with references to Australian plants and animals. Although he was sometimes able to sell work for considerable sums, his financial position was always somewhat precarious (no surprises there), leaving the Boyds and their growing family living in ‘an indefinable, vaguely Boehemian style of artistic poverty.’3

All of Merric and Doris Boyd’s children – Lucy, Arthur, Guy, David and Mary – learned the elements of pottery at an early age, helping out in the family business. Following the end of the Second World War the pottery entered a new phase, with the young Arthur (Merric Bloomfield) Boyd, in partnership with his colleague and friend John Perceval4, establishing a new workshop next to the now disused Open Country pottery, which they named after Arthur’s grandfather, calling it the Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery. Together with the Viennese émigré Peter Herbst5, they manufactured goods for the Ministry of Labour and National Service, as well as making individual art pieces.

During the 1940s, the Boyds’ encampment at Murrumbeena became a haven not only for the family but also their friends, ‘becoming more and more a loose colony of artists and intellectuals – one of the very few enclaves … to offer protection to radical modernists.’6 A similar group of artists gathered around John and Sunday Reed at Heide, a farmhouse located in the outlying Melbourne suburb of Heidelberg. There was some interaction between the two groups, with the artists Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester7, all names closely associated with Heide, visiting the Boyds at Murrumbeena. In addition, many figures who would go on to be well-known figures in Australian ceramics worked at or at least had contact with the Boyd workshops, including Carl Cooper, Tom Sanders and Hatton Beck.

David Boyd, who was a talented pianist, initially studied music at the Melbourne Conservatorium. In 1945, following his military service, he transferred his Commonwealth Retraining Grant to the National Gallery School where, following in his parents and grandparents footsteps, he embarked on a career in the visual arts. Studying drawing under the famous but rather conservative artist and teacher Sir William Dargie, Boyd soon rebelled. He moved to Sydney where one of his brothers, Guy, had already re-located in order to study sculpture at the National Art School with Lyndon Dadswell. During 1946 the two brothers became involved in a pottery enterprise, with David making a final move to Sydney in 1947. The colourful, popular ware they made was sold under the name of Martin Boyd Pottery, again following a confusing family tradition of naming workshops after members of the family who actually have no ties to the business being conducted, in this case David’s expatriate novelist uncle.

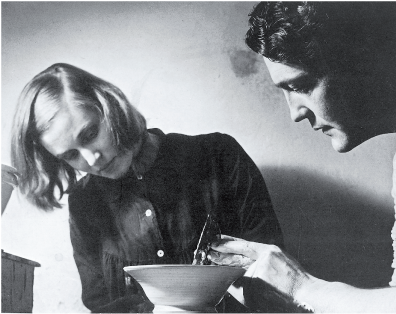

In the period between David’s initial contact with the business in 1946 and his return to Sydney in 1947, Guy had employed several fellow students from the National Art School to help in the workshop. One of these was Hermia Lloyd-Jones, a young and precociously talented artist who came from a family background that bore some similarities to that of the Boyds.

David and Hermia soon became a couple in life as well as in ceramics. In addition to the successful commercial ware, they began work on a group of ceramics primarily intended for exhibition and, in 1949, these works were shown at the Little Gallery at the David Jones department store. The Daily Telegraph’s art critic wrote:

‘It is rare to find produced in this country works of art which may, in both technical and aesthetic achievement, be judged by world standards. In the pottery of David and Hermia Boyd, that distinction is reached … It is a show not to be missed by collectors and those who are interested in the beginning of an epoch in Australian art.’8

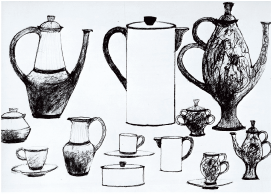

In 1950, David and Hermia Boyd, as so many other Australian artists had done before them, travelled to England. Having obtained a licence to sell their pottery from the Board of Trade, issued9 through the Crafts Council of Great Britain, they soon found a ready market for their pottery in many fashionable London outlets. The British trade journals Pottery and Glass and Pottery Gazette featured their work, as did several lifestyle magazines and they were able to obtain a lucrative licence to produce items for the 1951 Festival of Britain.

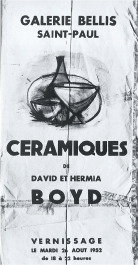

During this period the Boyds also spent a year in France, making pottery in the small village of Tourrettes-sur-Loup, positioned midway between Cannes and Nice in Provence. Returning to England, the Boyd’s resumed potting, including an exhibition at the Barling’s gallery in Mayfair and a stint designing work for the resurrected Chelsea Pottery, but, following a particularly cold English winter, they felt the urge to return to Australia. After rushing to fulfil a final order for Heals department store – worth around £3000, a very large sum of money for the time – the potters ‘returned in triumph to their homeland’.10

The Boyd’s successes abroad had been closely followed by the Australian press and their homecoming was accompanied by a blaze of publicity, or at least as much publicity as might reasonably be accorded to a pair of potters. The first exhibition held on their return, again at the Little Gallery at David Jones department store, was favourably reviewed, with The Herald’s art critic, Alan McCulloch, reporting that the pottery was ‘quite exquisite in design, shape and finish, and in fact much superior to anything of the kind that has so far been shown here.’11

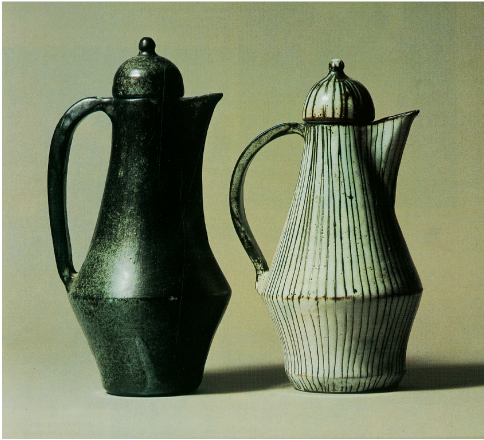

Over the next five years, David and Hermia Boyd continued to have regular sell-out exhibitions in the major cities, extending their formal language based on high-fired earthenware, original forms and decorations based on a marvellously fluent graphic sensibility and an extensive use of oxides (in particular manganese and copper) applied over or inlaid into commercial glazes.

At this point, in the mid to late 1950s, the stoneware pottery movement was in its formative stage with Harold Hughan in Melbourne and Ivan McMeekin and Peter Rushforth in New South Wales. By contrast, David and Hermia Boyd had around fifteen years of highly successful, innovative and lucrative ceramic practice behind them in England, France and Australia, with a string of sell-out shows meeting with critical acclaim, and involvement in commercial enterprises that had sold thousands of pieces of pottery. They were so far ahead of the game it’s difficult to see how, within another few years, they would be almost overlooked by the burgeoning Australian ceramics movement, and yet that is precisely what occurred.

Partly, this is because they decided to return to Europe in early 1962, following the awarding of an Italian government painting prize to David, who was increasingly concentrating on sculpture and painting as expressive mediums. At the end of this year the Boyds returned to England, where they would remain for much of the 1960s, and although they would continue to make ceramics to supplement their other artistic interests, their contribution to Australian ceramic life was effectively resigned to history.

Another reason David and Hermia Boyd’s contribution to Australian ceramics was overlooked was simply because they had worked exclusively in earthenware, when the orthodoxy of Leach-inspired Anglo Oriental ceramics was at its zenith. Colourful, earthenware ceramics, no matter how well done, were deemed to be old-fashioned, crass even, by the exponents of Antipodean Sung, who somehow overlooked Leach’s own enthusiasm for English slip-wares, which of course were also earthenware. For their part, David and Hermia Boyd held similar prejudices, having seen and dismissed much of British studio ceramics in the 1950s as being rather amateurish essays in a ‘recently evolved tradition’12,

with Hermia remarking on the preponderance of ‘Japanese squiggles or the Leach-introduced Eastern hieraglyphic [sic] for ripening corn’.13

Therefore, when the journal Pottery in Australia was first published in May 1962, with editor Wanda Garnsey taking pains to ‘acknowledge the stimulus of Bernard Leach’s personality … following his visit to Sydney’14, it’s hardly surprising that the recent, spectacular contribution of two generations of Boyds would be ignored, as indeed it was for many years to come. It is therefore entirely fitting that this article appears in the successor publication to Pottery in Australia and I can only hope that the contribution of the Boyds, and in particular that of David and Hermia Boyd, is re-assessed and appreciated by a new generation of Australian ceramic artists.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2009

- Emma Minnie Boyd nee a’Beckett, daughter of the first Chief Justice of Victoria, Sir William a’Beckett.

- Vader, J, p.18

- Niall, B, The Boyds: a family biography, Melbourne University Press, 2002

- Both Arthur Boyd and John Perceval went on to become very well-known and respected painters.

- Herbst went on to become Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National University and a founder of the Humanities Research Centre.

- Cochrane p. 70

- Sir Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester all become well-known painters. Sidney Nolan was also married to Mary Boyd.

- Vader, J p.27

- The Boyds’ licence to trade was issued by the Crafts Council of Great Britain against the wishes of its Director, the potter Heber Mathews. For a revealing glimpse into post-war British craft politics, see Vader, J, pp. 37–39

- ibid p. 107

- ibid p. 113,114

- ibid p. 36

- ibid p. 37

- Garnsey, Wanda, Editorial, Pottery in Australia, Vol. 1 No. 1, 1962