The Flying Scotsman

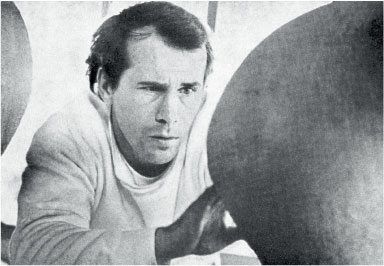

The last time Alex Leckie’s name was mentioned in dispatches, prior to news of his passing earlier this year, was in relation to the proposal in 2008 to close the ceramics department of the Glasgow School of Art.

Leckie’s name was inextricably linked to this institution. It was where he had begun studying in 1950 when, as the then Academic Registrar (Sir) Harry Barnes would later recollect, he was admitted ‘by the back door’, having shown a great deal of promise but possessing none of the normal qualifications to gain entry.1

It is unsurprising that the young Alex Leckie didn’t take to the disciplines of the post-war British education system, given his rather idiosyncratic upbringing. His father was an ardent communist and political activist who, nonetheless, instilled an appreciation of the arts into his son. The Leckie household library was extensive, containing several thousand books, and there were visits to art galleries and museums where he developed his appreciation of the work of ancient cultures, echoes of which would be found in his own ceramics in later years.

Leckie excelled at art school and was offered the chance to complete a Post-Graduate Diploma. A figurative vessel that was exhibited in that graduation exhibition is illustrated here, and demonstrates both his command of the medium and a remarkably early adoption of what would later become recognisable as his mature style.

In 1955, and in imminent danger of being called up for National Service, Leckie decided to move to Australia. Having relatives in South Australia he settled in Adelaide where he soon found employment throwing garden pots at Bennetts Magill Pottery, a job which he would later describe as providing ‘good discipline’.2 Enquiries at the South Australian School of Art led him to discover that he was the most highly qualified potter in South Australia, a situation which, rather ironically given his background, led to him being employed in 1956 as a teacher of ‘pottery and sculpture’.

It’s worth pausing at this stage to place Alex Leckie in the context of the early world of post-war Australian ceramics. When Leckie arrived in Australia, Ivan McMeekin, Ivan Englund, Peter Rushforth and Mollie Douglas were just establishing the Potters’ Society of NSW, Gwyn John (Hanssen Pigott) was still apprenticed to McMeekin at Sturt, Carl McConnell was active in Brisbane, Henri Le Grand was teaching in Canberra, Harold Hughan and members of the Boyd clan were taking their varying approaches to ceramics in Victoria, and there certainly were others – but not that many.

Considering where to place Leckie in this field is an interesting exercise. For a start, he was not a single-minded devotee of the Anglo Oriental approach espoused by Leach and Cardew, instead showing a preference for a modernist, European sensibility which brings to mind Picasso’s anthropomorphic ceramics. But Leckie also didn’t favour the rather commercial, high-keyed palette of earthenware, his surfaces instead relying on the subdued colours of clays and ochres, albeit enlivened by his use of colour and a marvellously dexterous feel for line and modelling. His ceramics refer back to the archaic forms which inspired him in his youth, where man and beast, male and female, entwine and merge in a sensuous dance with the medium of clay.

For all his undoubted technical and artistic abilities and a myriad of friends and supporters within the arts community, Leckie’s rebellious nature ensured that his tenure within the South Australian education department would not be without problems.

The by now well-known episode of Leckie swimming naked in the River Torrens and of his subsequent arrest (a seemingly trifling incident which provided front page titillation for the tabloid press and ultimately led to Leckie’s dismissal from his teaching post in 1962), introduced a surprisingly productive period during which he exhibited widely, undertaking many important commissions and becoming President of the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia. In 1964, he was one of three Australian ceramicists chosen to represent this country in the International Ceramics Exhibition in Tokyo, with his work, Destroyed City also appearing on the cover of Pottery in Australia. 3 4

In 1966, Alex Leckie decided to return to Britain. He spent a short time in London at the Central School of Art before returning to Scotland, where he was appointed Head of Ceramics at the Glasgow School of Art in 1968, a position he held for the next twenty years.

In an obituary published in The Scotsman, Jimmie Macgregor wrote that Alex Leckie ‘ ... took a moribund ceramics department by the scruff of the neck, completely transforming it and turning out students who were a credit to the school.’5

In all fairness, the Glasgow School of Art probably deserves considerable credit for keeping Leckie on staff for twenty years, as this ‘... wee bull who caused havoc in many a china shop ...’6 would certainly find difficulty adapting to today’s more politically correct academic setting. No more would a whole pig be roasted in the kiln as a contribution to Activities Week, but perhaps the managerial class which now largely controls the directions of art schools, on either side of the world, will doubtless rest easier at night.

When he left this country in 1966, Leckie was as well-credentialled as anyone, exhibiting nationally in prestigious galleries, working on architectural commissions and, above all, selling large amounts of his work to an appreciative public, all of which he achieved by the age of 35. He left behind many admirers, fond memories, some scandalous tales and an engaging and highly accomplished body of work. It is

to be hoped that an opportunity might exist in the not too distant future for the current generation of Australian ceramicists to be able to see a comprehensive exhibition of the work of Alex Leckie.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

- ‘Alex Leckie Ceramics’, an essay by Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes accompanying an exhibition at the St Enoch Exhibition Centre, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery.

- Ceramics in South Australia 1836 – 1986; from folk to studio pottery, Noris Ioannou

- Destroyed City by Alex Leckie, cover image, Pottery in Australia, Vol.3 No.2., October, 1964.

- In the end, four Australian potters were included in the International Exhibition of Ceramic Art in Tokyo – Alex Leckie, Milton Moon and Bernard Sahm were chosen by the various Australian selectors, whilst the Canberra-based potter Cecily Gibson was included following her extended residency in Japan.

- Appreciation: Alex Leckie, Jimmie Macgregor, The Scotsman, 12 February 2010

- ibid

Bennetts Magill Pottery Pty Ltd – a living history

Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

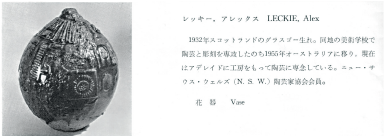

Currently in its fifth generation of family ownership, Bennetts Magill Pottery in Adelaide provides one of the last remaining glimpses into the small- to medium-size manufactory that was the mainstay of Australian ceramics throughout the nineteenth and into the first part of the twentieth century.

The founder, Charles (Chas) Bennett, was born in Somersetshire in England in 1842. In 1849 he travelled with his family to the newly established colony of South Australia, settling in Magill, then a semi-rural area a few miles east of the centre of Adelaide. Good supplies of clay, as well as abundant fuel in the shape of the string-bark forests cladding the adjacent hills, ensured the area quickly became home to a number of potteries, established to fulfil the needs of a rapidly growing population.

Photos: courtesy Mortlock Library, South Australia

The young Charles Bennett gained an apprenticeship at just such a pottery, run by a Cornish immigrant, third-generation potter named John Henry Trewenack. From the age of twelve, Bennett worked at Trewenack’s, first as an apprentice then as a full employee, where he spent many years learning about all aspects of the craft. In 1883, Charles Bennett, together with his son, William Charles Bennett, worked for a time at the nearby Piercy brothers pottery and it was there that the young William Bennett met his future wife, Abigail Piercy, forming a union that perhaps ensured the future importance of ceramics to the Bennett’s clan. Clay, it seems, was in their blood.

photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

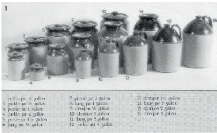

Following the death of William Piercy in 1885, the business went into decline, prompting the Bennetts to finally establish their own pottery on land the family owned at Magill. The pottery started trading at a date towards the end of the 1880s (the actual date is given variously between 1887 and 1890). Initially consisting of a shed, a horse-drawn pugmill and a small wood-fired kiln, the Magill Pottery Works, as it was called then, was gradually expanded to include a bottle-kiln, larger workshops and some mechanisation in the shape of steam or oil driven engines, thus relieving the horse of its more burdensome duties. Further equipment was added with the purchase of new throwing wheels manufactured by the English company of William Boulton Ltd, by which stage the pottery, now called C. Bennett and Sons, was producing a vast range of the kind of useful, no-nonsense pottery needed by homes, farms and industry – bread crocks and mixing bowls, preserving jars, acid, wine and spirit jars, butter coolers, poultry waterers, and garden and chimney pots.

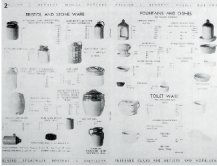

During the 1920s and 1930s, the pottery, now under the management of William Bennett, continued to increase the range of goods on offer. In addition to an assortment of terracotta pots there were several types of glazed domestic wares, although, in keeping with the mainstream of Australian ceramic practice, no fine dinnerware was produced, this market being met by imported English ceramics. Further to this, a range of highly successful ‘art pottery’ was produced, with vases and other decorative items being glazed in a variety of mottled and streaked lead-based colours, often referred to as Majolica or agate wares.

photo: Damon Moon

There were, however, setbacks. On the morning of 27 November 1940, a fire razed the building to the ground, leaving a total damage bill of around ten thousand pounds. The pottery was rebuilt, but by the time an official of the Department of Mines visited the factory in 1946, the pottery had returned to its core production, where:

Bennett’s products are largely confined to a stoneware and coarse domestic ware. Acid jars are thrown on the wheel ... Bristol ware is ... [made] ... from Tea Tree Gully clay with some Woocalla ball clay added to extend the vitrification range.1

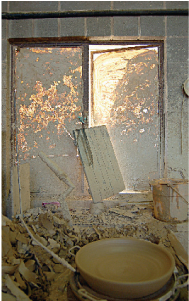

By 1950 the pottery was being run on a day to day basis by the third-generation William Reginald Bennett. The kilns were now fuelled by oil, which, unfortunately, did not prevent a second massive fire from destroying the pottery in 1956. Reginald Bennett seriously considered whether to rebuild the pottery, but since his own son, Robert William Bennett, was now working at there, it was decided that the business would continue.

In 1964, Robert assumed control, in a marketplace where conditions were changing rapidly. Although the majority of garden wares used in Australia were still produced locally, the lifting of post-war restrictions had allowed an ever greater amount of imported ceramics to enter the market, a move which led to the demise of many of the small manufactories which had sprung up in the immediate post-war years. Bennett’s responded to this decline by diversifying their manufacturing base, for a time even supplying bricks to a booming building industry, but also, conversely, by sticking to their guns and continuing to make a range of utilitarian pots almost identical to those they made in the late nineteenth century. A growth of interest in the crafts throughout the 1970s saw these traditional pots come back into fashion, while the proliferation of ceramics courses and increasing numbers of practitioners provided a ready market for Bennett’s clay. With the closure of Koster’s Pottery in 1977, Bennett’s was left as the sole South Australian pottery operating along more or less traditional lines.

In the mid-1970s, Robert’s son, John William Bennett, became the fifth generation to work at the pottery, and he now runs the business in a family lineage that spans three centuries. The last twenty or so years have seen added pressure on the business from imported garden wares, but Bennetts endures, providing a fascinating link to the vernacular ceramic traditions of the past.

Photo: courtesy Bennetts Pottery

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

A Family Affair – the Boyds and the History of Australian Ceramics

If Australia can lay claim to having an artistic dynasty, it is to be found in the Boyds. This country has produced many worthy artists but there is no other family that can boast members who rose to prominence in the fields of painting, literature, architecture and ceramics, and did so over several generations.

It is well known that many of the Boyds made ceramics, but what is unusual is the depth of their familial or collective involvement and the way ceramics were seamlessly integrated into a life of rich artistic endeavour. The Boyd’s involvement in the arts can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, to Arthur Merric Boyd snr and Emma Minnie Boyd1, both accomplished painters who had studied at the Royal College of Art in London. They had three children: Martin, who would become a well-known novelist, Penleigh, who was hailed as one of Australia’s most promising young painters until his untimely death in 1931, and William Merric, who would become the first Australian artist potter.

As a young man, William Merric Boyd (who is generally just known as Merric Boyd) studied art at the National Gallery School in Melbourne. Legend has it that during a trip to a commercial pottery to buy modelling clay for a sculpture class he was asked if he would like to try his hand at throwing a pot. It is recorded that he threw a perfect pot at his first attempt, an event that has undoubtedly been subject to exaggeration over the years, but nonetheless points to an early affinity for the medium of clay.2 Merric Boyd decided to become an ‘art potter’, working from a studio on a block of land the family purchased for him at Murrumbeena, a suburb then on the semi-rural outskirts of Melbourne. In 1912 Merric Boyd became a part of ceramic history by holding the first one-person exhibition of pottery in Australia at Centreway, a gallery in Collins Street in Melbourne. In 1915 he married Doris Gough, a fellow student from the National Gallery School, and she went on to work closely with Merric Boyd, decorating many of his ceramics over the subsequent years. By the time Merric Boyd left Australia in 1917 to fight in the First World War he was already a well-known ceramic artist.

Following his discharge from the army in England in 1918, he spent a year studying at the Wedgwood factory in Stoke-on-Trent, financed by a Commonwealth Rehabilitation Grant. On his return to Australia he resumed work at Murrumbeena where his ceramics met with considerable success. In keeping with the times he worked in earthenware, throwing pots which were then heavily modelled and decorated – often by Doris Boyd – in a faux-naïve style replete with references to Australian plants and animals. Although he was sometimes able to sell work for considerable sums, his financial position was always somewhat precarious (no surprises there), leaving the Boyds and their growing family living in ‘an indefinable, vaguely Boehemian style of artistic poverty.’3

All of Merric and Doris Boyd’s children – Lucy, Arthur, Guy, David and Mary – learned the elements of pottery at an early age, helping out in the family business. Following the end of the Second World War the pottery entered a new phase, with the young Arthur (Merric Bloomfield) Boyd, in partnership with his colleague and friend John Perceval4, establishing a new workshop next to the now disused Open Country pottery, which they named after Arthur’s grandfather, calling it the Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery. Together with the Viennese émigré Peter Herbst5, they manufactured goods for the Ministry of Labour and National Service, as well as making individual art pieces.

During the 1940s, the Boyds’ encampment at Murrumbeena became a haven not only for the family but also their friends, ‘becoming more and more a loose colony of artists and intellectuals – one of the very few enclaves ... to offer protection to radical modernists.’6 A similar group of artists gathered around John and Sunday Reed at Heide, a farmhouse located in the outlying Melbourne suburb of Heidelberg. There was some interaction between the two groups, with the artists Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester7, all names closely associated with Heide, visiting the Boyds at Murrumbeena. In addition, many figures who would go on to be well-known figures in Australian ceramics worked at or at least had contact with the Boyd workshops, including Carl Cooper, Tom Sanders and Hatton Beck.

David Boyd, who was a talented pianist, initially studied music at the Melbourne Conservatorium. In 1945, following his military service, he transferred his Commonwealth Retraining Grant to the National Gallery School where, following in his parents and grandparents footsteps, he embarked on a career in the visual arts. Studying drawing under the famous but rather conservative artist and teacher Sir William Dargie, Boyd soon rebelled. He moved to Sydney where one of his brothers, Guy, had already re-located in order to study sculpture at the National Art School with Lyndon Dadswell. During 1946 the two brothers became involved in a pottery enterprise, with David making a final move to Sydney in 1947. The colourful, popular ware they made was sold under the name of Martin Boyd Pottery, again following a confusing family tradition of naming workshops after members of the family who actually have no ties to the business being conducted, in this case David’s expatriate novelist uncle.

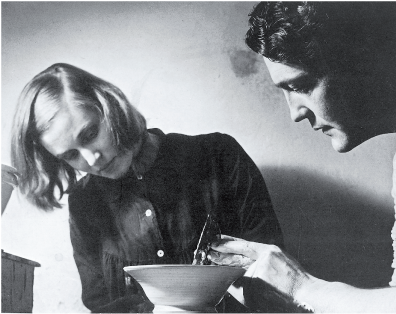

In the period between David’s initial contact with the business in 1946 and his return to Sydney in 1947, Guy had employed several fellow students from the National Art School to help in the workshop. One of these was Hermia Lloyd-Jones, a young and precociously talented artist who came from a family background that bore some similarities to that of the Boyds.

David and Hermia soon became a couple in life as well as in ceramics. In addition to the successful commercial ware, they began work on a group of ceramics primarily intended for exhibition and, in 1949, these works were shown at the Little Gallery at the David Jones department store. The Daily Telegraph’s art critic wrote:

‘It is rare to find produced in this country works of art which may, in both technical and aesthetic achievement, be judged by world standards. In the pottery of David and Hermia Boyd, that distinction is reached ... It is a show not to be missed by collectors and those who are interested in the beginning of an epoch in Australian art.’8

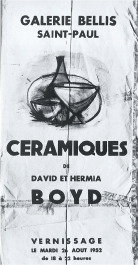

In 1950, David and Hermia Boyd, as so many other Australian artists had done before them, travelled to England. Having obtained a licence to sell their pottery from the Board of Trade, issued9 through the Crafts Council of Great Britain, they soon found a ready market for their pottery in many fashionable London outlets. The British trade journals Pottery and Glass and Pottery Gazette featured their work, as did several lifestyle magazines and they were able to obtain a lucrative licence to produce items for the 1951 Festival of Britain.

During this period the Boyds also spent a year in France, making pottery in the small village of Tourrettes-sur-Loup, positioned midway between Cannes and Nice in Provence. Returning to England, the Boyd’s resumed potting, including an exhibition at the Barling’s gallery in Mayfair and a stint designing work for the resurrected Chelsea Pottery, but, following a particularly cold English winter, they felt the urge to return to Australia. After rushing to fulfil a final order for Heals department store – worth around £3000, a very large sum of money for the time – the potters ‘returned in triumph to their homeland’.10

The Boyd’s successes abroad had been closely followed by the Australian press and their homecoming was accompanied by a blaze of publicity, or at least as much publicity as might reasonably be accorded to a pair of potters. The first exhibition held on their return, again at the Little Gallery at David Jones department store, was favourably reviewed, with The Herald’s art critic, Alan McCulloch, reporting that the pottery was ‘quite exquisite in design, shape and finish, and in fact much superior to anything of the kind that has so far been shown here.’11

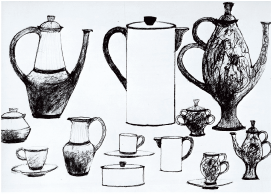

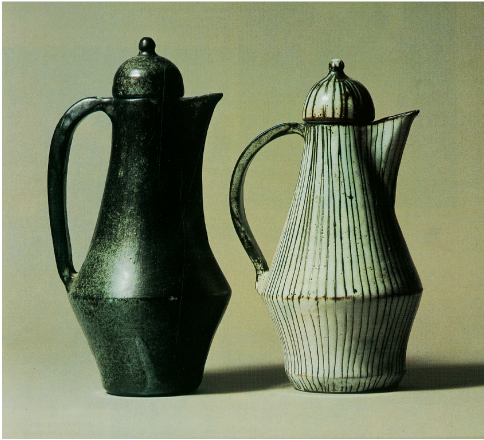

Over the next five years, David and Hermia Boyd continued to have regular sell-out exhibitions in the major cities, extending their formal language based on high-fired earthenware, original forms and decorations based on a marvellously fluent graphic sensibility and an extensive use of oxides (in particular manganese and copper) applied over or inlaid into commercial glazes.

At this point, in the mid to late 1950s, the stoneware pottery movement was in its formative stage with Harold Hughan in Melbourne and Ivan McMeekin and Peter Rushforth in New South Wales. By contrast, David and Hermia Boyd had around fifteen years of highly successful, innovative and lucrative ceramic practice behind them in England, France and Australia, with a string of sell-out shows meeting with critical acclaim, and involvement in commercial enterprises that had sold thousands of pieces of pottery. They were so far ahead of the game it’s difficult to see how, within another few years, they would be almost overlooked by the burgeoning Australian ceramics movement, and yet that is precisely what occurred.

Partly, this is because they decided to return to Europe in early 1962, following the awarding of an Italian government painting prize to David, who was increasingly concentrating on sculpture and painting as expressive mediums. At the end of this year the Boyds returned to England, where they would remain for much of the 1960s, and although they would continue to make ceramics to supplement their other artistic interests, their contribution to Australian ceramic life was effectively resigned to history.

Another reason David and Hermia Boyd’s contribution to Australian ceramics was overlooked was simply because they had worked exclusively in earthenware, when the orthodoxy of Leach-inspired Anglo Oriental ceramics was at its zenith. Colourful, earthenware ceramics, no matter how well done, were deemed to be old-fashioned, crass even, by the exponents of Antipodean Sung, who somehow overlooked Leach’s own enthusiasm for English slip-wares, which of course were also earthenware. For their part, David and Hermia Boyd held similar prejudices, having seen and dismissed much of British studio ceramics in the 1950s as being rather amateurish essays in a ‘recently evolved tradition’12,

with Hermia remarking on the preponderance of ‘Japanese squiggles or the Leach-introduced Eastern hieraglyphic [sic] for ripening corn’.13

Therefore, when the journal Pottery in Australia was first published in May 1962, with editor Wanda Garnsey taking pains to ‘acknowledge the stimulus of Bernard Leach’s personality ... following his visit to Sydney’14, it’s hardly surprising that the recent, spectacular contribution of two generations of Boyds would be ignored, as indeed it was for many years to come. It is therefore entirely fitting that this article appears in the successor publication to Pottery in Australia and I can only hope that the contribution of the Boyds, and in particular that of David and Hermia Boyd, is re-assessed and appreciated by a new generation of Australian ceramic artists.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2009

- Emma Minnie Boyd nee a’Beckett, daughter of the first Chief Justice of Victoria, Sir William a’Beckett.

- Vader, J, p.18

- Niall, B, The Boyds: a family biography, Melbourne University Press, 2002

- Both Arthur Boyd and John Perceval went on to become very well-known and respected painters.

- Herbst went on to become Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National University and a founder of the Humanities Research Centre.

- Cochrane p. 70

- Sir Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester all become well-known painters. Sidney Nolan was also married to Mary Boyd.

- Vader, J p.27

- The Boyds’ licence to trade was issued by the Crafts Council of Great Britain against the wishes of its Director, the potter Heber Mathews. For a revealing glimpse into post-war British craft politics, see Vader, J, pp. 37–39

- ibid p. 107

- ibid p. 113,114

- ibid p. 36

- ibid p. 37

- Garnsey, Wanda, Editorial, Pottery in Australia, Vol. 1 No. 1, 1962

A State of Flux: The Future of Australian Ceramics Education

Appearing under the banner 'Scotland's Last Ceramics Course to Close', the March 2008 article from the Glasgow Sunday Herald discussed the imminent demise of ceramics at the Glasgow School of Art. Responding to concerns raised by current students, ex-students and staff – one of whom was the potter Alex Leckie, an influential figure who worked in South Australia as far back as the late 1950s – the article quoted a statement released by the school, which reads as follows.

'Across our other design programmes, competition for places is very high. In contrast, a growing lack of competition for places within ceramic design represents a significant risk to Glasgow School of Arts academic reputation and makes it difficult to ensure that consistency of student attainment is maintained across the design programme.'

I do think the phrase 'significant risk' is worth highlighting, as we all know just how dangerous ceramics can be.

This press-release mirrored, albeit rather bluntly, a conversation I had recently with the Dean of an Australian art school, one of a diminishing number where ceramics is still offered as part of the syllabus. The phrase this person used concerning the future of ceramics was, and I quote: 'Between you and me, mate, it's buggered', a comment which at least dispensed with the management-speak emanating from the GSA.

Ceramics, it seems, is well on its way to becoming a historical oddity, a phenomenon which had taken off in the post-war era and would fizzle out in the early twenty-first century, only to be remembered as a minor curiosity of Australian art history. Some even thought they could pinpoint the time when Australian ceramics began its decline. Apparently it occurred at a meeting of the Australia Council in the early 1990s when the crafts were amalgamated with the visual arts for funding purposes, resulting in the creation of the dreaded level playing field.

This view sheets home any current difficulties to a time when ceramics began to be treated in the same way as the rest of the visual arts, something which, in all fairness, many ceramists had wanted for years. I take another view, in attributing the current malaise to the fact that ceramics had already started to mimic the rest of the visual arts, in the mistaken belief that the rich, complex and often puzzling world of contemporary art somehow lacked enough things made out of clay. In doing so, it neglected to value its own craft traditions, while at the same time it largely failed to assume the critical rigor that would validate its participation in the fine arts.

This mostly came about because ceramics, for quite some time now, has been solely taught within an art school system transfixed by the razzamatazz of contemporary art, an enterprise so successful at marketing, public relations and branding, that what is being presented hardly matters. The money that is thrown at contemporary art is quite staggering, and I would guess that the budget for Australian representation at the Venice Biennale alone overshadows any federal funding for the crafts. Only today — as I was putting the finishing touches on a wood-kiln, of all things — I was stunned to learn that a tabloid newspaper in Adelaide had opined that what the city really needed was a Guggenheim! I'm guessing that this wasn't because the editors were desperate to see more contemporary art, but simply that they had heard about the brand. I doubt that suggestions of building a small annexe to house the Art Gallery of South Australia's wonderful collection of Thai and Cambodian ceramics would be met with such journalistic enthusiasm.

Yet, given the primacy of contemporary art within the education system and its overwhelming presence in the cultural landscape, it is no wonder that some ceramics departments began taking on some of the more dubious benefits of a theory-laden environment which had become part and parcel of art school education.

Earnest discussions took place about Gaston Bachelard, who had written a book called The Poetics of Fire– perhaps it was mistaken for a book on kilns? Julia Kristeva was abject and Jacques Derrida was everywhere, causing otherwise perfectly normal people to look po-faced and babble about the concept of difference in a silly French accent. In a bid to reign in the confusion, a leading art school paid a philosopher (as opposed to a hack art theorist) to come down from Melbourne Uni one morning and answer questions from the student body. I still remember seeing a hand being raised during question time and hearing a small voice ask, 'Please, can you tell me what hermeneutics are?', sounding for all the world like the urchin Oliver asking for more food in the poorhouse.

In an unfortunate coincidence, the uncertainties of post-modernism coincided with a series of amalgamations in higher education, implemented in a policy called the Unified National System thought up by John Dawkins, Hawke's education minister from 1987 to 1990. Doing away with CAEs, Teachers Training Colleges and the like, this collection of new and expanded universities were soon to be subjected to the strictures of economic rationalism, first with Keating and then increasingly under the Howard regime. At a time when universities were forced to offer a plethora of courses in management and business studies to fee-paying students just to stay afloat, it is quite obvious that the humanities, and particularly the arts, would suffer. (In fact, one could also say the same things about the sciences. I was in the geology department of a major university the other week where basic analytical equipment was not maintained in working order and there was no longer a technician, which, given the importance of minerals and mining to the Australian economy, is a bit of a worry.) That these financial strictures never seem to affect the budget for new buildings is one of life's great mysteries.

Still, it is hard to think of any course that is more vulnerable within a financially stretched, economically-rationalised university than a course in ceramics. And, quite frankly, it is hard to think of any course that is more ill-suited to being taught within a university.

Luckily, and perhaps inevitably, the decision of how to reconcile these glaring contradictions seems to have been taken out of the hands of most art school ceramics departments within universities, due to the simple fact that they are closing down.

The reality is that there are now very few art schools - or TAFES for that matter – offering any training in ceramics at all. The 'elephant in the room' of Australian ceramics education in 2008 is that of the art schools which do still offer ceramics, only a few are able to do their job properly, due to the severe cutbacks in staff and equipment which have plagued them for years.

Again, let me stress that there still are some places where the training is of a good standard – I won't single them out but it's pretty obvious where they are – but they are precious few and diminishing as we speak. So, the question is, what are we to do about all of this?

For a start, I'd give up on the idea of a large scale reinvigoration of ceramics within the art school system. It's not going to happen, and I'm not sure it should even if it could. Most art schools never really considered ceramics as part of their 'core business' anyway and to hang around when it is obvious one is not wanted is undignified. But there are alternatives approaches that might be taken, and one of them is as follows.

Someone who wants to learn how to make pottery should be able to work with a skilled, mature practitioner in a thorough, ongoing, comprehensive fashion in a workshop-based environment.

I am not talking about the current system of mentoring here, in that mentoring normally involves taking someone who already has decided on a form of individual expression and then pairing them with an experienced practitioner who gives sage but occasional advice, although this doubtless has its benefits. What I am talking about is a system where a student enters a workshop and is trained in the style and philosophy of the teacher. In six months a student could easily learn more workshop skills in this way than in three years in an art school ceramics department.

Of course, their experiences would largely be shaped by the type of work made by the teacher, but surely a student would choose a teacher because they liked their style of work in the first place? Perhaps this might be called a traineeship mentorship as opposed to emerging (and don't we all love that term?) mentorship. Instead of looking at mentoring as an activity that occurs towards the end of an art school education, maybe a traineeship mentoring scheme would be valuable as a precursor to art school, at least ensuring that the student goes into further education with some basic skills.

Whether a student was interested in wood-firing, funky sculptural work or slick and reductive porcelain, the main repository of expertise and knowledge — as opposed to information — rests, quite literally, in the hands of experienced makers, most of whom do not work in art schools. This is a resource that is going begging, as far as education is concerned.

As someone who has numerous degrees, including a doctorate in art history, I am very aware of the significant role an academic training in the arts plays in educating, informing and challenging one's views.

Equally, I can say without doubt that my grounding in actually making pottery was gained through working with my father — one of this countries most respected potters and someone who doesn't have a degree to his name – and in time spent working in production potteries, in travelling and visiting museums, in meeting with other potters and simply by looking at and handling pots in the company of others who also knew and cared about pottery. This is the way many people used to learn. It is the way Gwyn Hanssen Pigott learned as did her teacher, Ivan McMeekin and it makes a good deal of sense.

In conclusion, I do not advocate the wholesale scrapping of art school ceramics training. Institutions like the Jam Factory in Adelaide and Sturt Workshops in New South Wales also play an important part, as do the plethora of associations, collectives and clubs around the country. I do want to see a healthy diversity in educational options and workshop based training should play an increasingly important role in the future.

And no, I don't know how this is to be achieved. Maybe students should think about other ways that a $5,000 a year HECS debt could be made to work for them, or if the Austudy payment of approximately $175 per week, with all its entanglements in the bureaucracy of Centrelink, is the deciding factor as to whether one studies at an art school or comes to a private arrangement with a teacher. Maybe a teacher should consider just how much they would want for their services?

All I can say is that I would consider very seriously any requests that came my way.

Damon Moon

Willunga, 2008

Kirsten Coelho — Studio Potter

There have been many changes over the years in the terms used to describe those who find personal expression in the manipulation of clay. The November 2005 exhibition by Kirsten Coelho at the BMG Gallery in Adelaide provides a welcome opportunity to write about the work of someone who fits – quite precisely – a currently underused epithet, that of 'studio potter'.

In these days of ceramicists (a word, predictably enough, recognised by Microsoft Office 2000 spell-checker) ceramic artists (flesh and blood, really) designer-makers with a ceramics-based practice, and a dwindling number of potters, the term studio-potter is refreshingly transparent. We understand immediately an engagement with a discipline that constitutes one of the core traditions of 20th century craft; one which is, thankfully, still alive and well in the new millennium. Kirsten Coelho is an exponent of such an approach, where late-nineteenth century European sensibilities met a thousand years of North-Asian ceramics to create an idiom which whilst finding a home in craft, could reach out with one hand and touch art, and with the other the practical world of industry. None of this describes what Coelho’s pots are like, but it helps in understanding where they come from; what they are, and what they are not.

bowl h.7.5cm, d.26cm, vase h.24cm.

Photo: Grant Hancock

If one had to cite the antecedents of Coelho’s work the names would be unsurprising. There is an element of Lucie Rie, of Sung and T’ang pottery, even of Gwyn Hansen-Piggott, though without recourse to the device of still-life. She has chosen impeccable models, and in adding her own voice to this lineage of quietude, the message is carried forward, altered and enriched.

Coelho’s pottery is now recognisable, and in this exhibition these familiar themes are restated and refined. The straight-sided bowl, small cups and tapering vases, along with newer essays in form; a long-necked bottle and tall lidded-jar, both of which acknowledge their Chinese ancestry whilst living very much in the here and now. The clay is porcelain; the glazes variations of celadon, temmoku, copper-red, and an unctuous white which ranges in surface quality from silken-matt to being slightly glassy and reflective. It is mostly to this white glaze that Coelho has added touches of iron, just a spot or thin line, which lightly pulls at the waist or touches the lip. These marks address the form so intimately that I would hesitate to describe them as decoration; they are more a kind of visual punctuation, giving lift and cadence to the object.

Interestingly, Coelho often refers to these marks as coming from her observations of corroded metal, especially the ubiquitous galvanised-iron rainwater tank that, together with a Eureka lemon tree, was found in most Adelaide back yards before the heady days of gentrification and urban infill. Her home-studio in an old workers cottage is in an area of the city where industry has also left its share of detritus. This may seem an unexpected source of inspiration for the beauty of porcelain, yet the district’s history as a port adds a layer of complexity, as this fragile substance has a long history of trade.

Coelho has recently been awarded an Australia Council residency in London, a city where she has spent many years and to which she owes much of her ceramic development. It seems only fitting that she returns there periodically, as there is a sensibility about her work that is very English. Not the England of Cool Britannia & YBA’s, and certainly not the England of Grayson Perry, which, despite the noise and clamour for attention, is only a very small part of the whole. I suspect Coelho’s London touchstones are to be found in the Victoria and Albert, the Percival Pavid Foundation or Gallerie Besson, rather than in the Saatchi Collection or Tate Modern. And, away from the city, there are still many potters of note, who, like Richard Batterham, pursue their profession, making objects of simple beauty and unquestioned authority.

Photo: Jim DeGregorio

This is not to say that this approach to ceramics is nostalgic or stultifying, or that it has failed to happily assimilate ideas, styles and techniques from many different places. It is more about the pace at which change takes place, and a healthy scepticism of change for changes sake. In the tradition of which Coelho partakes you only take a step forward when you are sure you understand the last. The past is not seen as something to be challenged and defeated; it is instructive, and therefore nurturing. The territory it occupies, between art and industry, is exactly where it wants to be, because it constructed, or at least redefined, this in-between place. Despite the odd revisionist declarations of a new breed of craft theorists, its engagement with multi-culturalism has often been marked by a degree of respect and sensitivity that the fine-arts can only dream about.

All of these things may be found to varying degrees in the best studio-pottery, and they are to be found in the work of Kirsten Coelho.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2006