Perspective

“I cross the room like a dancing architect

A daddy waltz on the tops of my shoes ...”

Let’s face it – architects are cool. They wear good clothes, have distinctive taste in spectacles and build fabulous, titanium clad post-modernist cathedrals to art which rejuvenate entire cities. Even in the fraught and over-hyped world of contemporary art it’s obvious that the star attraction of the Bilbao Guggenheim is the building and its architect, Frank Gehry, and not the art inside.

On the other hand, ceramists are not really cool and probably never have been. There may have been a certain cachet afforded to the hand-spun, tie-dyed and hirsute in the 1960s, but ceramics has really always been just this side of macramé as far as the mainstream arts establishment goes, and it probably always will be.

Given this, it might seem strange that in the early days of the post-war Australian crafts movement architects featured prominently in generating support for the crafts. They encouraged craftspeople to extend their vision by commissioning works for buildings, by helping with exhibition design, by collecting works to be shown in their own and in client’s houses, and by participating in an active dialogue as to how the built environment and the hand-made object might co-exist in the modern world.

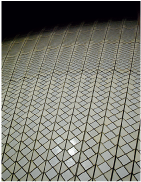

Sydneysiders should be more aware of this than most, since they have in their midst one of the greatest examples of twentieth century architecture in the shape of the Danish architect Jorn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, a building totally covered with white ceramic tiles. One might fairly ask if the tiles, made by the Danish firm Höganäs, are the product of craft or industry, or indeed are any more significant than the ubiquitous clay bricks from which the majority of Australian houses are constructed. But what this building represents, at least in part, is the emphatic arrival of a Scandinavian design aesthetic in Australia, and with it the promise of an integration of crafts and industry, an ideal which now probably falls into the category of ‘nice work if you can get it’ but which, nonetheless, had much currency at the time.

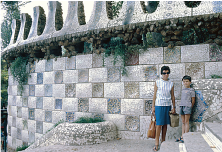

If only a few modern buildings were entirely covered with ceramic tiles – and, after all, the Muslim world had taken this technique to heights of extreme beauty and sophistication hundreds of years before – then the fifties and the sixties also saw a rebirth of interest in other ways to marry ceramics to architecture. One was in the use of mosaics, with perhaps the greatest example being Antonio Gaudi’s Guell Park in Barcelona, where the order and discipline or the traditional tiled ceramic surface is literally shattered into a colourful, fragmented universe of inspired crazy-paving.

A related use of architectural ceramics was found in feature walls or panels, which had the advantage of being able to be either outside or inside a building, due to the ability of ceramics to cope with harsh environments. The artistic partnership of the painter Joan Miro and ceramicist Jose Llorens Artigas gave us monumental outdoor panels in the 1957/59 Wall of the Sun and the Wall of the Moon for the Unesco Building in Paris, work so important that it led to Miro receiving a Guggenheim award in 1958. (Ironically, these artworks are now enclosed by a building in order to protect them from the effects of acid rain. Perhaps ceramics are not quite as durable as we think ...) Some Australian examples of public ceramics murals, as in Vincent McGrath’s three metre by eleven metre Wall, completed in 1980 for the Attorney General’s Department in Alice Springs, are mentioned in an excellent article by Romaldo

Giurgola, one of the architects of the new Australian Parliament House. This article, first published in 1984 and now reprinted in this issue of The Journal of Australian Ceramics, gives an insight into how one of this country’s leading architects sought to incorporate the work of Australian craftspeople into the very fabric of this important building (if that isn’t mixing metaphors) right from the planning stages.1

On a more intimate scale, the interiors of 1960s architect-designed modernist houses, with an emphasis on natural surfaces largely free from overt ornamentation, provide a wonderful setting for ceramics of the period. There is a certain ‘rightness’ in seeing stoneware ceramics displayed in this setting, whether as tiles, functional pottery or decorator pieces.

For example, in the ceramics of Marea Gazzard one sees a sophisticated take on the vessel as domestic sculpture. Before studying in Europe in the 1950s, Marea Gazzard, who was married to the architect Don Gazzard, had been exposed to the work of avant-garde British ceramic artists like Lucie Rie in the pages of influential architectural magazines like Domus. In England she had contact with Rie, as well as with the work of the artists Nicholas Vergette and Hans Coper, and it was Coper’s work in particular that deeply informed Gazzard’s ceramics on her return to Australia in 1960.

At the time, only a few Australian potters were experimenting with forms beyond the purely functional. It is true that many potters had made smaller scale sculptural pieces – John Percival’s famous Angel works are a good example – but it is a mistake to confuse this work with ceramics which have a more direct connection to architecture.

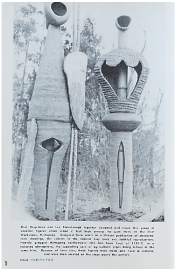

These connections are sometimes obvious, as in the incorporation of ceramics into a building or

its surrounds; at other times they are more indirect. Sometimes it is just a question of scale, as when the Austrian-born sculptor Bert Flugelman collaborated with Les Blakebrough on large scale ceramic sculptures that were made and subsequently exhibited at the Sturt Workshops in Mittagong. To pick a more contemporary example, Deborah Halpern’s well-known artwork Angel (not to be confused with the Percival ones), originally sited at the entrance to the National Gallery of Victoria and now found

at Birrarung Marr park on the banks of the Yarra River, is architectural in nature not only because of

its scale but through its intent, in that it was commissioned to be a part of a building or its immediate surrounds. This is seen quite literally in the visual pun of the sculptor Aleks Danko’s, Songs of Australia Volume 3, At Home sited in the courtyard facing the JamFactory Craft and Design Centre, the Experimental Art Foundation and the entrance to UniSA’s City West Campus in Adelaide.”

It seems likely that the emphasis has shifted in contemporary architectural ceramics in Australia, from large-scale public commissions to community-based projects. However, given the obdurate nature of the material and its intrinsic connections to the built environment, ceramics will probably always find some place in the architecture of the day.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

- I feel it is reasonable to claim Romaldo Guirgola as Australian since, although he was born and trained in Italy and has spent much time living in America, he took up Australian citizenship in the 1980s.