The Flying Scotsman

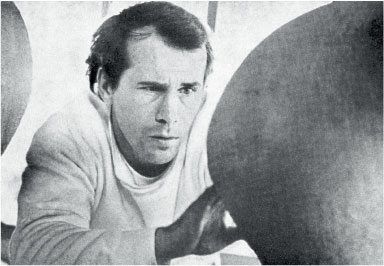

The last time Alex Leckie’s name was mentioned in dispatches, prior to news of his passing earlier this year, was in relation to the proposal in 2008 to close the ceramics department of the Glasgow School of Art.

Leckie’s name was inextricably linked to this institution. It was where he had begun studying in 1950 when, as the then Academic Registrar (Sir) Harry Barnes would later recollect, he was admitted ‘by the back door’, having shown a great deal of promise but possessing none of the normal qualifications to gain entry.1

It is unsurprising that the young Alex Leckie didn’t take to the disciplines of the post-war British education system, given his rather idiosyncratic upbringing. His father was an ardent communist and political activist who, nonetheless, instilled an appreciation of the arts into his son. The Leckie household library was extensive, containing several thousand books, and there were visits to art galleries and museums where he developed his appreciation of the work of ancient cultures, echoes of which would be found in his own ceramics in later years.

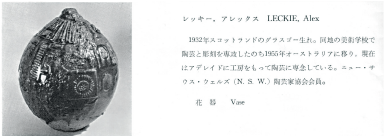

Leckie excelled at art school and was offered the chance to complete a Post-Graduate Diploma. A figurative vessel that was exhibited in that graduation exhibition is illustrated here, and demonstrates both his command of the medium and a remarkably early adoption of what would later become recognisable as his mature style.

In 1955, and in imminent danger of being called up for National Service, Leckie decided to move to Australia. Having relatives in South Australia he settled in Adelaide where he soon found employment throwing garden pots at Bennetts Magill Pottery, a job which he would later describe as providing ‘good discipline’.2 Enquiries at the South Australian School of Art led him to discover that he was the most highly qualified potter in South Australia, a situation which, rather ironically given his background, led to him being employed in 1956 as a teacher of ‘pottery and sculpture’.

It’s worth pausing at this stage to place Alex Leckie in the context of the early world of post-war Australian ceramics. When Leckie arrived in Australia, Ivan McMeekin, Ivan Englund, Peter Rushforth and Mollie Douglas were just establishing the Potters’ Society of NSW, Gwyn John (Hanssen Pigott) was still apprenticed to McMeekin at Sturt, Carl McConnell was active in Brisbane, Henri Le Grand was teaching in Canberra, Harold Hughan and members of the Boyd clan were taking their varying approaches to ceramics in Victoria, and there certainly were others – but not that many.

Considering where to place Leckie in this field is an interesting exercise. For a start, he was not a single-minded devotee of the Anglo Oriental approach espoused by Leach and Cardew, instead showing a preference for a modernist, European sensibility which brings to mind Picasso’s anthropomorphic ceramics. But Leckie also didn’t favour the rather commercial, high-keyed palette of earthenware, his surfaces instead relying on the subdued colours of clays and ochres, albeit enlivened by his use of colour and a marvellously dexterous feel for line and modelling. His ceramics refer back to the archaic forms which inspired him in his youth, where man and beast, male and female, entwine and merge in a sensuous dance with the medium of clay.

For all his undoubted technical and artistic abilities and a myriad of friends and supporters within the arts community, Leckie’s rebellious nature ensured that his tenure within the South Australian education department would not be without problems.

The by now well-known episode of Leckie swimming naked in the River Torrens and of his subsequent arrest (a seemingly trifling incident which provided front page titillation for the tabloid press and ultimately led to Leckie’s dismissal from his teaching post in 1962), introduced a surprisingly productive period during which he exhibited widely, undertaking many important commissions and becoming President of the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia. In 1964, he was one of three Australian ceramicists chosen to represent this country in the International Ceramics Exhibition in Tokyo, with his work, Destroyed City also appearing on the cover of Pottery in Australia. 3 4

In 1966, Alex Leckie decided to return to Britain. He spent a short time in London at the Central School of Art before returning to Scotland, where he was appointed Head of Ceramics at the Glasgow School of Art in 1968, a position he held for the next twenty years.

In an obituary published in The Scotsman, Jimmie Macgregor wrote that Alex Leckie ‘ ... took a moribund ceramics department by the scruff of the neck, completely transforming it and turning out students who were a credit to the school.’5

In all fairness, the Glasgow School of Art probably deserves considerable credit for keeping Leckie on staff for twenty years, as this ‘... wee bull who caused havoc in many a china shop ...’6 would certainly find difficulty adapting to today’s more politically correct academic setting. No more would a whole pig be roasted in the kiln as a contribution to Activities Week, but perhaps the managerial class which now largely controls the directions of art schools, on either side of the world, will doubtless rest easier at night.

When he left this country in 1966, Leckie was as well-credentialled as anyone, exhibiting nationally in prestigious galleries, working on architectural commissions and, above all, selling large amounts of his work to an appreciative public, all of which he achieved by the age of 35. He left behind many admirers, fond memories, some scandalous tales and an engaging and highly accomplished body of work. It is

to be hoped that an opportunity might exist in the not too distant future for the current generation of Australian ceramicists to be able to see a comprehensive exhibition of the work of Alex Leckie.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2010

- ‘Alex Leckie Ceramics’, an essay by Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes accompanying an exhibition at the St Enoch Exhibition Centre, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery.

- Ceramics in South Australia 1836 – 1986; from folk to studio pottery, Noris Ioannou

- Destroyed City by Alex Leckie, cover image, Pottery in Australia, Vol.3 No.2., October, 1964.

- In the end, four Australian potters were included in the International Exhibition of Ceramic Art in Tokyo – Alex Leckie, Milton Moon and Bernard Sahm were chosen by the various Australian selectors, whilst the Canberra-based potter Cecily Gibson was included following her extended residency in Japan.

- Appreciation: Alex Leckie, Jimmie Macgregor, The Scotsman, 12 February 2010

- ibid